|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites and Documents >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

One Gun, 11 Victims

They are stolen, bought and traded to the point that, for city police, it's hard to tell any gun they seize from all the others. But one stood out. |

One Gun, 11 Victims (PDF, one page) |

|

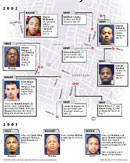

As Hartford police investigated a series of shootings over seven months in 2002, the gun got their attention. It was a sleek, black Glock 9mm. By the end of the year, it would be used to shoot 11 young men. Two of them died. Even though the cops eventually got the Glock off the streets, they were never able to figure out exactly how many gunmen used the gun in the course of its bloody spree. They arrested four men on charges of illegally possessing the Glock, including a teenager who was convicted Thursday of using it to shoot and kill a man from the suburbs who had come to Hartford to buy drugs. But the cops came to believe that it had been in more hands than that, many more. They gave it a label. A "community gun," they called it, the kind of gun that falls into the wrong hands and then is loaned out, "rented" or sold within a circle of young men who hang out together on the street. The gun came to exemplify the difficulty that cities such as Hartford have in keeping guns out of the hands of young people. But all that came later. In May 2002, when police responded to the shooting of a young man at Garden and Capen streets, they had no reason to believe they were dealing with anything unusual. It seemed like another dime-a-dozen shooting with another dime-a-dozen gun. The Trail Begins The corner at Garden and Capen is one of the busiest intersections in the North End, a place where the traffic rarely dies down and people bustle in and out of the mom-and-pop shops that line the sidewalks. But late at night, the thumping of car stereos and the shouting and laughter of people eventually give way to quiet. Which is why the pop-pop of gunfire shortly before midnight on May 21, 2002, drove people out of bed to call police. Before the cops arrived, the shooting victim, 23-year-old Edward Bennett, had staggered to his home several blocks away on Acton Street, bleeding from gunshot wounds in his shoulder and back. One of Bennett's relatives called 911, and police raced to his home on the second floor of a rundown apartment house. Bennett told officers, "I ain't telling you ... nothing," then demanded an ambulance. But as paramedics were treating him, Bennett gave the cops some information. He told them he and his "boy," an unidentified friend, had been sitting in a parked car at Garden and Capen when a gunman walked up to them and opened fire. The friend, who was not hit, refused to tell the cops anything - an all-too-common response in the city. Bennett was taken to the hospital, and detectives went to the shooting scene to scour the area for clues. Amid the discarded cigarette packs and food wrappers that littered the sidewalk, detectives found several shell casings from a handgun, though police couldn't tell exactly what kind of handgun they had come from. The detectives collected the casings, making sure each was properly marked and recorded as evidence, the same routine as in any other shooting. The casings would be sent to the state police forensics laboratory for ballistics testing to see if they had markings that could be matched to a particular gun, maybe one that had been used in other shootings. The testing, which analyzes the unique markings left on the casings by a gun's firing pin, would take weeks to complete because of the painstaking nature of the work. But detectives had no reason at that point to make the Bennett shooting a higher priority than other cases, so they continued looking for witnesses and pumping Bennett for more information. Whoever used the Glock that night kept it in circulation. It would be heard from again, soon. Little To Go On Just a few blocks from Garden and Capen, on a downtrodden stretch of Enfield Street, 16-year-old Matthew Cauley was standing astride his bicycle while talking to a group of friends. It was about an hour past midnight on Sunday, June 30, and the air was heavy and humid. Cauley, a student at Weaver High School, glared as a car full of young men slowly drove past. The men in the car glared back, but the car kept rolling. A few minutes later, the car returned, and Cauley and his friends could see that the men inside were concealing their faces with the hoods of their sweat shirts - a sure sign that trouble was about to pop. One of the men pointed a gun out of the car's window and announced, "We're back. ... What you gonna do?" Then gunfire erupted, and Cauley, grimacing in pain, fell to the pavement, hit in the arm and leg. When the police arrived, they couldn't get any of the kids who were hanging out with Cauley to give them a good description of the men in the car. The case was closed a few months later when Cauley told police he didn't want the investigation to go any further. Like other kids who get shot in Hartford, Cauley felt it would be safer for him not to talk because he didn't want to labeled as a "snitch." But at least one of the kids was willing to cooperate a little the night Cauley was shot, showing cops where the shooting had taken place. Detectives found several shell casings and submitted them to the forensics lab. As with the Bennett case, the casings appeared to be from a handgun - maybe a Glock - but that was about all detectives could find out. At the forensics lab in Meriden, ballistics expert Jim Stephenson began comparing the shell casings from the Bennett shooting with those taken from the Cauley shooting. It would be weeks before his analysis, which required microscopic examination of the markings on each of the shell casings, would be complete. And the Glock was still out there. More Clues Two weeks later, on another humid night, 30-year-old Eugene Williams was walking with his friend Willie Kinder, 30, on Garden Street when a car approached them slowly. Williams told police he and his friend sensed there might be trouble when the car's headlights flicked off as it rolled up alongside them. "I had a funny feeling and I was thinking that the people in the car were going to rob us and take our little bit of money," Williams said. "Willie must have been thinking the same thing when he saw the car because he said, `Oh, it's about to go down.'" Several young men sat in the car, all of them wearing dark sweat shirts. Two of them pointed guns out the window and started firing. Williams, shot in the thigh, fell to the ground. So did Kinder. The gunmen continued firing, then drove away."We were like playing possum and they just shot at us and then drove off," Williams said. He and Kinder helped detectives locate more than a dozen shell casings on the street. The detectives once more collected the casings - more remnants of handgun ammunition - and submitted them to the lab. They again put their faith in Stephenson and other experts at the state ballistics lab. Bullet fragments found at many of the crime scenes were too damaged to test. So, using a sophisticated new computer system, Stephenson set out to create digital images of the shell casings to determine if the markings would match up. Then he would have to line them up himself, under a microscope, to know for sure. A Mysterious Figure The heat of summer had taken a thorough hold of the city by the end of July that year. The only relief for many residents came late at night, when the air cooled down a bit. Darrell Hundley, 24, was one of several people hanging out on Elmer Street in the predawn hours of July 31. He was sitting on a lawn chair beneath the glare of a streetlight, talking to some girls in a parked car. Suddenly everyone scattered as gunshots erupted from across the street. Hundley, whose twin brother was shot and killed in Hartford in 1995, jumped into the back of the girls' car after a bullet struck him in the ankle. His friends drove him to the hospital, where they told police they saw a shadowy figure firing shots from a shaded area between houses. But they said it was too dark to see who the gunman was. Detectives found shell casings in the grass and submitted them to the lab. For the cops, the summer was shaping up to be a hot one, and not just in terms of the weather. After a relatively peaceful spring, the number of shootings in the city was beginning to rise, due largely to an outbreak of turf wars and robberies among rival groups of young men in the North End. The Glock was right in the middle of it. A Break, At Last A week later, 16-year-old Albert Perry and his friend 17-year-old Alvin Wilson were walking from a convenience store on Albany Avenue, where they had gone to buy snacks about 1:30 a.m. on Aug. 7. On a dark stretch of Magnolia Street, a masked gunman ran up to them and ordered them to sit on the ground. He told the teens to hand over the cash in their pockets. Perry later told the cops he gave up his cash, but Wilson refused. The gunman opened fire, shooting Wilson twice and grazing Perry on the hand. Doctors had to remove Wilson's right kidney and repair punctures to his liver and diaphragm. At the scene, detectives recovered a single shell casing, which went to the forensics lab. Police were still waiting for the lab results when, on Aug. 12, they were sent to Milford Street to investigate the shootings of Donald Raynor, 17, and Timothy Browdy, 21. The cousins had been talking to each other when a gunman shot at both of them from a passing car. Raynor told the cops he heard the glass shatter in the car he was sitting in, then spotted a green car speeding away as he realized he was shot in the upper back. Browdy, who suffered more serious injuries after being shot in the stomach, provided few other details when he was interviewed several weeks later. Detectives were gathering shell casings from the scene when Stephenson called to give them the test results for which they had been waiting 11 weeks. The casings collected at the shootings between May 21 and Aug. 7 were fired from the same gun, he said.More particularly, he said, the gun was a Glock 9mm, Model 17, that appeared to be several years old. Finally, a breakthrough. "It was a `eureka!' moment," said Stephenson, a former New Haven detective who has become a national expert in ballistics testing. "The evidence spoke for itself." The Glock, Easy To Get A few weeks later, Stephenson contacted the Hartford detectives again to let them know the same gun had been used to shoot Raynor and Browdy, as well as Joseph St. Pierre, 36, who was wounded at the corner of Asylum Avenue and Sigourney Street on Sept. 12. Now, detectives knew that a single gun had been used to shoot eight people in the course of 16 weeks. And even though they had not made any arrests, they were beginning to get the idea that more than one person was using it. They pressed informants on the street for information on who might have the Glock. The informants, along with some of the witnesses in the shootings, said the gun was changing hands among a group of men in their teens and early 20s who hung out on Oakland Terrace and other side streets off Albany Avenue. Police learned that some of them had been feuding with rival groups of youths who lived near Enfield Street and Barbour Street, which may have explained some of the shootings in those neighborhoods. The night he was shot, Perry told detectives he suspected the gunman was a guy who lived along Albany Avenue who regularly robbed people. Though he did not give the cops a name, Perry said the gunman had told him and Wilson that the black handgun he was pointing at them "was not his but he could get it anytime he wanted to." Getting Creative That tip from Perry gave the cops a glimpse into the countless ways that illegal guns reached the city's streets and then changed hands. There is no single pipeline for guns into Hartford that can be easily plugged; there are so many streams into the city that law enforcement officials admit they pretty much have to search for illegal guns one at a time. Ammunition is easy to get, too. "Tracing a gun is like trying to trace a dollar bill," said Kevin O'Connor, the U.S. attorney for Connecticut. "Guns can find their way to the streets in dozens of ways, hundreds of ways." Detectives know many of the guns on the street had been stolen in house burglaries, while others had been bought in illegal "straw" purchases in which a legitimate buyer purchases a gun and then gives it to someone else. Others get their hands on guns by making connections in states where gun-buying laws are more lenient than Connecticut, such as Vermont, or Southern states such as South Carolina. They might go to those states and buy several guns to bring back to Hartford, or they might ask relatives who live in those states to buy guns for them. Some teens and young adults get pretty creative. Some trade heroin or crack for guns. In 2003, a 15-year-old boy arranged to rent a handgun for $40 from a Hartford man for a week. The boy, who lived in Wethersfield but went to Hartford every day to deal drugs on Farmington Avenue, later pleaded guilty to manslaughter after he used the gun to kill another man he was trying to rob. "If people want a gun, they're gonna get it," said Robert Taylor, 37, who used to sell drugs in a North End housing project and continues to stay close to friends who trade in guns and drugs. "These kids feel they're vulnerable without a gun." Contrary to popular perception, Taylor said, buying a gun in Hartford is not a simple matter. "You can't just walk up to somebody on the corner and get him to sell you a gun," he said. "They might think you're a cop, or working for a cop. You have to know somebody first." Detectives tracing the Glock found that it came from a plant in Georgia and was first sold at a gun shop in Virginia in 1991. From there, the trail went cold. They never learned how it made its way to Hartford. Two MurdersThrough the fall of 2002, those who had been shot by the Glock had all recovered. But that was about to change. On Dec. 5, Stacey McDonald, 20, was driving with a girlfriend down Granby Street about an hour before the sun came up. As he cruised toward the intersection of Granby and Plainfield streets, McDonald was shot in the head by a gunman firing from a passing car. He died instantly as his car crashed into a utility pole about a block from an elementary school. Detectives canvassed the scene that morning as curious schoolchildren walked by. They gathered more shell casings that seemed to be a match for a Glock and submitted them to the lab. Then, on a bitter cold night just a couple of days after Christmas, 31-year-old Scott Houle of East Hampton turned his car onto Cabot Street hoping to find someone to sell him crack. It was past midnight, but Houle spotted a group of teenagers leaving an apartment house. The group included 16-year-old Rondell Bonner and his 15-year-old uncle, Calvin King. Just minutes before, Bonner had been holding the Glock, toying with it as some of the other kids scrawled graffiti on the mailboxes in the building's entryway. As they saw Houle approaching in his Kia Sportage, Bonner and King flagged him down to sell him drugs. Bonner handed him a plastic bag full of crack as they negotiated a price. Then things got tense, and one of the boys shouted, "He's trying to play us!" Bonner pulled the Glock from the waistline of his pants, and, police say, he and King, who also had a gun, began firing. Houle, a father of four young girls, was shot in the head and died as his car slid into a fence. Bonner and King raced to Bonner's home on Sargeant Street, where they changed clothes. Police say Bonner, who would be arrested three months later after detectives tracked down witnesses to the crime, gave the Glock to King and told him to sell it. Stacey McDonald's mother, Sarah Johnson-Ellis, said the case of the Glock shows Hartford has become too dangerous for families who want to keep their children safe. "Look at all the people who were harmed by this gun. And it was just one gun," said Johnson-Ellis, who moved to Georgia after her grandson was shot and killed a few months after McDonald's slaying. "It's too much. All the kids have guns now, it seems like." In the course of seven months, the Glock had been used to wound nine people and kill two. Houle would be the final victim. It would take months more for police to finally get the Glock off the streets. Seizing The Glock In March of 2003, police arrested Bonner on a murder charge, though King had not yet been linked to the crime. The same month, police say, King was allegedly selling the Glock to Tyree Downer, who lived in the same neighborhood where the gun was circulating. Downer bought the gun for $400. He sold it in May to Eon Whitley, 26, who knew Downer from the time they served together in a juvenile detention facility. Police say Whitley bought the gun for $350 while they ate lunch at a Jamaican restaurant. By that time, the cops had been able to link the gun to Downer through informants. When they questioned him, Downer said he had already sold it to Whitley. They were getting closer, but when police pulled Whitley over during a traffic stop in July, he said he had already sold it for $400 to Robert Crowe, 29, who lived near Downer. Facing a possible charge of illegally buying and selling a handgun, Whitley agreed to set up a buy from Crowe. In late July, Whitley met with Crowe on Winter Street and bought the gun back for $395. Whitley turned the gun over to police, who submitted it for testing. Bonner, King, Downer and Crowe were all charged with illegally possessing the Glock. Whitley was not charged, after cooperating with police. Downer was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in prison in 2004. Crowe was convicted and sentenced to two years in prison. No one has been charged in connection with McDonald's death or the shootings of the other nine victims. But the community gun was off the streets. It's now in a cardboard box, evidence at Superior Court in Hartford- Exhibit A in the murder trials of Bonner and of King, who was arrested on a murder charge in 2004. Bonner was convicted Thursday of illegally possessing the Glock and killing Houle. King is awaiting trial on charges of criminal possession of the Glock and killing Houle.

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 | |

||

|