|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | |||

|

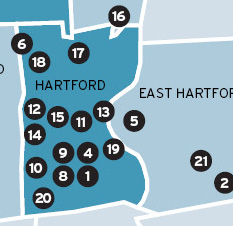

A Decade of Half Measures 10 years after a Hartford mother and son forced city schools to integrate, progress has dragged July 23, 2006 Eugene Leach couldn't help himself. He's a historian after all. Our conversation was about Sheff vs. O'Neill - the landmark Hartford school desegregation court ruling that is 10 years old this month. The Trinity College history and American studies professor took me back to 1848 and the writings of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, one of his favorite 19th century authors and orators. Douglass had been lamenting the construction of a new school in Bath, N.Y., with taxpayers' dollars. It was going to be for whites only. He believed segregated schools were unbecoming and shortsighted. "It will be an important point gained if we secure this right," Douglass wrote. "Let colored children be educated and grow up side by side with white children, come up friends from unsophisticated and generous childhoods together and it will require a powerful agent to convert them into enemies and leave them to prey upon each others rights and liberties." Those thoughts 158 years ago are as profound today - and as difficult to attain. The Sheff plaintiffs are once again haggling with the state, urging more progress in the desegregation of Hartford schools. A decade after the court's decision that Hartford's schools would be integrated voluntarily, the 24,000-student school district remains 95 percent black and Latino, and most of the students are poor. While some city students now have better opportunities to be educated, most continue to languish in substandard public schools. The problem is that these students' futures are subject to the luck of the draw - or the school lottery, in this case. And, as the kids might say, that sucks. "I'm where Douglass was in 1848," said Leach, who is white and a parent-plaintiff in the Sheff suit. "I haven't changed my fundamental belief that what the country professes is equality. And equality means open doors for integrated education and open opportunity for integrated education." The state Supreme Court ruling on Sheff was national news. That the state was deemed responsible for de facto segregation, even thought it didn't cause it, was a largely contrarian notion. The verdict came seven years after the suit was filed in 1989 and one year after Superior Court Judge Harry Hammer had ruled in the state's favor. Still, even with the trumping Supreme Court edict - which suggested no remedy - the plaintiffs had to return to court three times in arguing that the state was not complying. A settlement was finally hatched in 2003, in which both sides agreed that the state would build eight new magnet schools over four years at a cost of about $45 million per year. A separate program, called Open Choice, was established to increase the number of suburban-school slots available to city students from 1,000 to 1,600. The goal was to have 30 percent of the Hartford students in integrated schools by 2007. The state has fallen way short on all of these goals. Its administrators have blamed construction delays and problems finding suitable building sites. Only two magnet schools are in new buildings, with others in various stages of planning. Of the 1,600 suburban-school seats available to Hartford students, only 1,062 have been filled. Educators say increases in suburban populations have made fewer of those seats available. Other observers suggest that political will is also a factor. With the 2007 deadline approaching on the settlement, my assessment of the 1996 verdict is that it is one fraught with frustration and anticipation. After all these years, Sheff, much to the plaintiffs' chagrin, gets a grade of "Incomplete" - just a notch above an F. "If you go back to the overall goal of reducing racial isolation and economic isolation, not much has changed in that regard," said Eddie Davis, the recently retired Danbury schools chief. He was the Hartford school superintendent in 1996. "It's great to see the theme schools that are beginning to spring up around the Hartford area, and yet they have attracted a very small number of white students," he said. "If you had not been here 10 years ago and didn't know about the Sheff lawsuit, you'd see very little evidence that there was a lawsuit and that the plaintiffs prevailed." Take a snapshot of the Hartford schools today and you'd get a blurry picture. But if you pieced together a montage, not all the views would be out of focused. Since 1996, there have been noteworthy and surprising developments in the efforts to integrate and improve the education of minority children: Twenty-two magnet schools have been established - a few before Sheff, and many as a result of the case. Most are in various stages of being built or rehabilitated. Hartford runs 12 magnets; the non-profit Capital Region Education Council runs most of the others. Suburban students being drawn to the 12 Hartford-run magnet schools are mostly black and Latino, not the white schoolmates the plan was devised to attract. The eight schools run by highly regarded CREC, however, are drawing white suburban students at percentages that meet or exceed the targeted 30 percent threshold. All of the CREC magnets, five of which are in Hartford, are up and running and performing reasonably well. But only two of the 12 Hartford-run magnets - Greater Hartford Classical Magnet and Noah Webster Micro Society Magnet - are in buildings where construction has been completed. Hartford's Breakthrough Magnet elementary school opens in a new building in the fall. Charter schools were not part of the Sheff solution. Elsewhere in the state, however, are encouraging - though isolated - examples of publicly funded, independently run charters increasing test scores while educating concentrations of poor African-Americans and Latinos. State supreme courts in Kentucky and Oregon are looking at the legality of so-called "voluntary desegregation" efforts such as the Sheff agreement and will ultimately determine whether to disband them. While the plaintiffs and the state quibble about progress, there's no denying that most Hartford parents have more choice than ever - albeit with a lottery system - in choosing schools for their children. For many of the top magnet schools, the waiting lists are up to three times greater than the school's capacity. Without question, the demand from urban parents for quality schools remains high. Frustration over the implementing integration is equally high. It reached a point where John Brittain - the attorney who helped the plaintiffs win their case and became one of the most prominent faces of the Sheff case - started having second thoughts. If meaningful change couldn't happen even with a state Supreme Court ruling, Brittain fumed, maybe he should have agitated more for quality neighborhood schools instead of integrated ones. Though still an advocate for integration, Brittain says generations of young urban children have been sacrificed while integration efforts lag. "I don't think integration is dead, but certainly it's in the intensive care unit," said Brittain, now the chief counsel and senior deputy director of the Washington, D.C.-based Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. "And it's certainly losing its enthusiasm among the intended beneficiaries of communities of color. ... The Sheff vs. O'Neill decision largely has met the same fate as its fore-parent, Brown v. the Board of Education, in the long delay and difficulty in implementation." Fifty-two years after the landmark Brown decision ruled segregated schools were illegal, America's public schools are re-segregating at a pace comparable to the 1950s. Stanley Battle, a former administrator at Eastern Connecticut State University, now is president of Coppin State University, a historically black university in Baltimore. Coppin also oversees a largely minority K-12 public school system, which is beginning to show academic strides because of the schools-university partnership. Battle said he's long past pining for integration to improve urban education, though he sees the value of diverse classrooms. "We talk about integration, but we practice segregation. Let's be honest,"' Battle said. "So, if we're so hell-bent on saying one thing and doing another, let's at least be honest about making sure that the schools are at the highest quality, that we have certified and top-notch teachers, that we have good equipment, partnerships and relationships with universities, the private sector and businesses to encourage children to stay in school." African-Americans and Latinos represent 22 percent of Connecticut's total population but 75 percent of its prison population. Of the states 18,000 prison inmates, 75 percent don't have high school diplomas. In many states, including Connecticut, there are more black men in prison than in universities. And while Connecticut has some of the finest public schools in the country, it has the nation's widest academic-achievement gap between African-American and Latino students and their white peers. "We have to find different paradigms to make sure that we don't have a legacy of children who are totally ignorant," said Battle. Norma Neumann-Johnson is in her 38th year as a Hartford educator. She is the principal and founder of Breakthrough Magnet School, scheduled to open its new $29.5 million, 59,000-square-foot building on Brookfield Street in September. Breakthrough's theme is character development. Some 307 students from pre-school to eighth grade are expected to attend this fall, but there is a waiting list of about 1,200. Nearly one-third of the enrollment will be white. Neumann-Johnson - who is of Irish, German and Norwegian descent and has interracial children - is adamant about how a culturally diverse classroom promotes academic excellence. "The classroom is transformed by diversity and multiple economic levels being together," Neumann-Johnson said. "We need to take a stand for this and actually include it in our speaking, that we believe in this, that this is what is healthy and needed particularly when you look at all the divisiveness in the world." Demographers predict that by 2050, America will be made up primarily of non-whites. So, why not get future generations of Hartford area youth accustomed to engaging other cultures? "The state has not met the goal of the settlement and has not honored the ruling from the Supreme Court," said Hartford City Councilwoman Elizabeth Horton Sheff. Her son, Milo, now a rapper, is the plaintiff for whom the case is named. "While minimal progress has been made, the state is not fully committed to the desegregation of our schools." The state is asking for patience, saying that building eight new schools in four years is an ambitious undertaking. "What's complicated is trying to find sites that are available for school buildings in a city like Hartford, where the city is fairly justified in being reluctant to give up land that could be taxable," said Jack Hasegawa, the state Department of Education's bureau chief for educational equity. "And the city's school-building stock is pretty well used up." Of the 3,050 students in its eight magnet schools, 42 percent are white. The schools, by most accounts, are clean and orderly ,and their students do relatively well academically. The regional consortium's success has caused other educators and community people to ask, quietly for now, why the state doesn't simply hand over management of all the magnet schools to the organization. Bruce E. Douglas, executive director of CREC, says the Hartford-run magnets just need time - time to open their new buildings, time to market their themes and time to establish a track record. The CREC magnets have already done that. They're not only attracting white suburban students but also outside educators who are visiting and taking a look. School officials from Raliegh, N.C., recently visited CREC's Metropolitan Learning Center in Bloomfield so they could take notes on its global- and international-studies theme. The themes at the CREC-run schools, along with new buildings and strong partnership with local municipalities, are giving CREC a competitive edge in the magnet game. The Greater Hartford Academy of Math and Science has partnerships with Hartford Hospital, Trinity College, the University of Connecticut Medical School and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Last spring, it was the first high school in the country selected to perform the Broadway "Cats." Douglas said CREC's approach is to develop educational themes so irresistible that the average white, suburban parent must take notice. Invariably, he said, the question from those parents will be why should they take their kids out of the top-quality school they're in now. "And you better be able to answer that question and produce on it," Douglas said. By having diverse educational settings and distinct education niches, Douglas can make his case that CREC students are better prepared for an eclectic 21st century work force. Also, Douglas said, the bureaucracy at CREC is "flat," meaning the response time to concerns or complaints from parents or staff is quicker than in public school systems whose hierarchy requires multiple levels of approval. As renewed talks between the plaintiffs and the state begin, one of the issues that must be advocated seriously is an agreement to let CREC run all the magnet schools. Hartford can play a role, but CREC, despite funding problems, should take the lead. Certainly politics and egos will get in the way of such a remedy, but the best argument for letting CREC run the show is its track record. Another solution that would make these magnets more appealing would be to build some in the suburbs or on Hartford's borders. Partnering the magnets with other non-magnet schools and with universities or businesses is an enlightened national trend worth replicating, too. Better accountability to measure progress needs to be agreed upon. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been pumped into these desegregation initiatives, including money for pre-school and literacy education. Martha Stone, a lead-plaintiff attorney, said a mechanism to measure progress will be among the items the Sheff team will be seeking in its next round of talks. That lack of measurement has raised the eyebrows of some third-party observers. "It's surprising to me in all the talk of school accountability lately that there's no legal mechanism to make sure that the quality of the academic achievement is under consideration," said Jack Dougherty, associate professor of education at Trinity College. Dougherty, along with other local professors, has been researching Sheff's impact. He said his research indicates that the state is overstating the percentage of Hartford students who qualify to be counted toward compliance with the Sheff settlement. The state's estimate is 23.5 percent; Dougherty's research shows it's 14 percent. The negotiations should also talk about significantly increasing the percentage of city students to be integrated. The current 30 percent goal means more than two-thirds of the Hartford kids are left behind. More incentives are also needed for suburban schools to open slots for city kids. If the Sheff goal is to be achieved, Open Choice can't be offered in name only. While there is a lot of angst about whether white suburban parents can be compelled to send their children to racially diverse magnet schools, there's evidence to show that plenty of parents greatly value diversity. More than half the students are white at three CREC-run magnates - Two Rivers Magnet Middle School in East Hartford, Greater Hartford Academy of Math and Science in Hartford and the Greater Hartford Academy of the Arts, also in the city. "We're Caucasian, so my son pretty much assumed that all white people stayed together and that we're all from the same neighborhood," she said. "To me, [cultural diversity] is very important." Caplinger, 28, said she had recruited five more white families, including a relative's, to sign up for the Breakthrough lottery. But oddly, Caplinger says, none were selected. Then there is Jacob Komar, the Burlington prodigy I met last year when he was 12. At age 2, he was writing computer commands on a laptop. At 5, bored with his teacher's rote teachings of the ABCs, he finally told her she was "insulting my intelligence."' His parents sent him off to private school and eventually he was taking classes at Tunxis Community College. Jacob finally decided to enroll at University High School in Hartford, a magnet school with a science and engineering niche. Soon to be located on the campus of the University of Hartford, it will also give students the opportunity to attend college classes while in high school. Jacob's the kind of kid who could wind up graduating from college before his peers are done with high school. To see this underage, skinny white kid from the sticks comfortable attending school with older African-American and Latino students speaks to the mission of Sheff and the writings of Frederick Douglass. Jacob told me that race didn't matter to him. What did matter was that the other kids also shared his interest in math and science. Jacob's dad, Andy Komar, said the diversity of the school was part of its allure because his son "could grow up being with other children who look like the rest of the world." Maggie McCarthy of East Hartford is white and a senior at Capital Preparatory School. The Hartford magnet high school has a white population of 18 percent but a mixture of cultures including Asians, West Indians, Russians, African-Americans and Indians. McCarthy wants to be a teacher. Exposure to a wide array of cultures now, she says, will make her a more productive teacher later. "I know that I'm going to be working with a bunch of different kids, so its good to branch out," she said. Isaiah Graham, 15, of Hartford is African-American and a sophomore at Capital Prep. He's thinking about a career in law and says the mixture of cultures at school expands his intellectual horizon. "With all these different people with different backgrounds and different experiences, everything from your learning experience to your classroom discussion is more unique," he said. Kimtuyen Tran, 15 and of Asian descent, says her generation is much more "open-minded minded to diversity" than their parents. She's right. As the world grows more culturally diverse, efforts like Sheff may one day become moot. The risk in doing an examination on the Sheff verdict 10 years later is that what may look like a simple finding could be misleading. If you probe Sheff and judge it solely on how the Hartford-run magnets are progressing, you could say the patient is dying of neglect. If your assessment is anchored on the CREC-run magnets, you could make the case that the Sheff agreement just needs a management transplant. Together, the findings represent both progress and struggle. I can almost hear Professor Leach now, quoting Frederick Douglass again. "There is no progress without struggle."

|

|||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

|||

|