|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

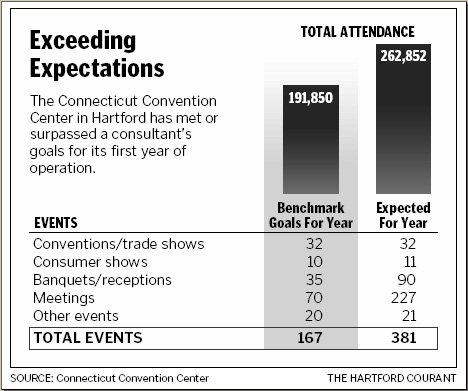

A Center Of Attention By Most Accounts, It's Been A Good First Year As Hartford Plunges Into The Convention World June 5, 2006 A year after the ribbon was cut, the Connecticut Convention Center has begun to do what it promised -- put feet on Hartford's streets, lay heads on Hartford's hotel bedsand and inject the city's downtown with new life. Bringing fencers and robotics teams, corporate lunches and groundskeepers, boaters and veterinarians, the center has hosted more than twice as many events as anticipated. Demand for city hotel rooms and the prices for those rooms increased at significantly higher rates than in previous years; and even though the center lost more money than anticipated, that was largely due to rising energy costs. Beyond the numbers, meeting planners say that the center's marketing team has worked hard at selling Hartford as a destination, and downtown business owners say they're seeing an early benefit from visitors. Conventioneers who have come and gone have left favorable responses. But some unsettled questions at the convention center threaten continued progress. Front Street -- the retail, residential and entertainment area that is to link Adriaen's Landing to the rest of downtown -- is still a vacant, 6-acre idea in the minds of people at the state, the city and a Greenwich developer. \\ More urgently, disputes between organized labor and the facility's operators threaten to drive away convention business, like the 2007 convention of the United Church of Christ, and sour relations between the mayor and one of his most-needed developers. \\ So just as the center picks up momentum, just as it begins to successfully market itself nationally as a facility in a city with a real desire to succeed, it risks losing its edge. By The Numbers The theory has long been that the number of events that come to the convention center isn't as important as the mix of events. A consultant hired years ago to plan for the facility's future set a benchmark for the first year: 32 conventions and trade shows, 10 consumer shows, 35 banquets and receptions, and 90 meetings and other events. That's 167 events.

Through the end of this month, the convention center is projected to meet those goals: 32 conventions and trade shows, 11 consumer shows, 90 banquets and receptions, and - note the jump - 248 meetings and other events, for a total of 381 events. "Do you have any concept of how difficult it is to sell a building that you can't feel and touch and walk into?" said Len Wolman, head of the Waterford Group, which operates the convention center and adjacent Marriott hotel. "In a city that had the reputation that Hartford had? And to have 381 events?" Wolman says that when the center was conceived, the state funding was hinged on $200 million in private investment in the city. Now, total investment in the city is up to $2 billion, he said. "This is one of those engines that really drives that," he said. The response from convention planners who have come and who soon plan to do so has been positive, praising the center's staff and those who sell it. "You cannot help but be impressed," said Maurice Desmarais, president of the International Business Brokers Association. "The convention bureau people have worked very hard to promote Hartford and to give it a new image, and that's important for people like me who do planning." Downtown restaurants such as Morton's steakhouse have seen a 25 percent spike in business since January, which they credit to the convention center. When Morton's takes reservations, it takes a phone number, too. And the numbers are often out-of-state cellphones. Not everyone is thrilled. Operators at the city's two other exhibition halls - the Civic Center and the Connecticut Expo Center - said they always thought that the convention center would be for conventions. As a result, they also thought that one of their core businesses - consumer shows - would be left untouched. Not so. "It shouldn't have happened," said developer Philip Schonberger, part owner of the Expo Center. His facility has lost several of its major shows to the convention center. He doesn't mind competition, Schonberger says. He and his staff just don't like being forced to compete against a new public facility that operates at a loss. "It's not fair to have our business stolen." Martin Brooks, general manager of Madison Square Garden Connecticut, which runs the Civic Center, sees the convention center as a complement to the city, allowing it to attract events that it otherwise would not. But even though his annual numbers are up, his consumer show business is down. "I'm talking about the trade shows, the business meetings, the dinners that were already occurring; I believe a lot of that type of business that the convention center had is not new to the market," Brooks said. But the convention center management isn't bashful about the center's potential for consumer shows, combined with the ability to work in conjunction with the Expo and Civic centers. Wolman says that the shows that have moved have grown. He pointed to the Connecticut Marine Trades Association, which was in Connecticut before at the Civic Center. But they didn't just move, Wolman said. They increased attendance by 50 percent and revenue at the gate by at least 70 percent, he said. "The shows bring a lot of people into town," Wolman said. "They don't necessarily drive a lot of [hotel] room nights, but it does drive a lot of business, and people begin to get used to coming downtown." The Missing Link Front Street has long been considered a keystone at Adriaen's Landing. A convention center is good for the tourists and the convention-goers, a science center is good for the family and the kids, but Front Street - the retail, entertainment, and residential district to be sandwiched between the convention center and the rest of the city - is what could tie what's new to the rest of downtown. But the road from idea to execution has been a long one. In August 2004, the Capital City Economic Development Authority dumped developer Richard Cohen when he failed to begin building two years after signing a contract with the state. Then, after a bungled attempt to find a new developer, the state began a third search. In April 2005 - two months before the convention center opened - the state chose the HB Nitkin Group of Greenwich as its final choice for "preferred developer," and the two sides began working toward a development agreement. About 10 months later, in February, Nitkin signed an agreement with the state that would bring 200 residential units and 100,000 square feet of retail space to Adriaen's Landing. The deal allows Nitkin to proceed in two phases. The first is a $31 million project with a minimum of 60 residential units and 43,000 square feet of rentable retail. But the city is not pleased with the agreement, and it is balking at immediately turning over $16 million in cash and tax abatements from the city. Hartford officials don't like the idea of phases, and they want Nitkin to commit to a more comprehensive project before it commits to providing millions in cash. Talks continue. A year ago, John F. Palmieri, the city's director of development services, said that one way to gauge the success of the convention center would be to see if Front Street is realized. One year later, the convention center is succeeding and the ground at Front Street is still unbroken. "Front Street would be a nice thing to have, but it's not essential in terms of the continued success of the convention center in the short term," said Hartford Mayor Eddie A. Perez. But, he added, "in the long-term - five, six years from now - you can't have a hole in the ground across the street." Labor Trouble The prospect of labor unrest has been telegraphed for years. Ever since then-Gov. John G. Rowland pushed ahead in the late 1990s on legislation for a new convention center and hotel that did not provide for the types of labor concessions at Adriaen's Landing that unions had hoped for, people close to the convention center have seen trouble looming. So the fact that it appears that the convention center lost a major convention - the 2007 gathering of the United Church of Christ - to the aging Civic Center might not be a total surprise. But left unaddressed, the lack of a consensus on labor issues at the convention center could spell long-term trouble. The center has an image to think of, and no convention facility - new or old - wants to be branded as a place that has union trouble. Plus, operationally, the center's management is in a tough spot. Don't concede, and the specter of picket lines and protests might chase more conventions away. Give up too much, and the convention center could become an overly expensive place to do business, which could also chase customers away. "Labor issues are a poison in our business," said James E. Rooney, executive director of the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority. "You get that reputation, and the meeting planners tend to want to go in another direction. And both in terms of space and in terms of places that union issues do not appear to exist, there's plenty of options out there." At the heart of the trouble is a dispute over how to organize workers. Unite Here!, the union seeking to organize convention center and hotel employees, has long contended that federal labor laws do not adequately protect workers who want to organize, making them vulnerable to intimidation and harassment. The union's national push to organize more service workers has come to Hartford, where Unite Here! wants Waterford to sign a "labor peace" agreement that would ensure greater protections for the workers during an organizing campaign in exchange for a promise from the union that it would not picket, boycott or protest. But Waterford has shown no signs of giving in, contending that it needs only to abide by the National Labor Relations Act. The state owns the convention center and blames the union for the current unrest. The city, which argues that its own statutes require Waterford to give in, is taking sides against Waterford. An attempt by Perez on Friday to pull the parties together fell short. But regardless of who wins the fight, and regardless of who's right, the center's image stands to lose. "It is very much a concern to the people that care about Hartford," said Michael Cicchetti, a spokesman for the Capital City Economic Development Authority. "We don't want all the work that's been made and the success that we've enjoyed to be taken away and derailed by this one entity." "It's a very delicate situation," he said. A spokesman for Unite Here! says that it is Wolman who is to blame. "It's a real shame that the success of this entire project is going to be jeopardized by Len Wolman's refusal to sit down and work things out," said union spokesman Antony Dugdale. Dugdale recognizes that labor unrest can hurt a facility. Part of the union's strategy is to turn up the public pressure. "But I also tend to think that if we were able to work things out, we'd be able to turn [the center's future] around," he said. Perez - who once called this "the most critical time for the convention center and the hotel," who said "it raises a lot of concerns for me and the folks on the city council," and who said that "labor unrest was not part of the equation" - has since changed his tune somewhat. "It's hard for me to believe that anybody would believe that that facility would be a private venue with no unionization effort," he said Friday. People who did not plan for labor unrest? Naive, Perez said. That all said, Perez said he believes that the time for bravado is coming to an end. "Now there's posturing," he said. "Eventually, there will be a reality that people will be at the table to discuss this. It may take some posturing on either side before they get real, and I think they'll get real in months rather than years." "We're trying to stabilize our reputation of, `Can we be in the big leagues?'" Perez said. "The answer is, we've got to solve these little questions if we want to be in the big leagues."

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|