|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | |||

New Wealth Stirs In An Old City

Seven months ago, with their children grown and after buying a second home on Cape Cod, the Daglios sold their house in Granby and moved to a downtown apartment. |

Is Urban Living Act II for the Baby Boomers? (PDF file, one page) |

||

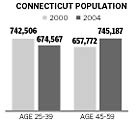

Once one of America's wealthiest cities, Hartford has hardly been a magnet for the affluent in recent decades. Households that earn more than $125,000, at least double the median household income in Connecticut, make up a significantly smaller share of the population in Hartford than in the nation's largest cities, and even in economically distressed cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore and Newark. But from downtown Hartford to the West End, developers are betting that aging baby boomers and a housing boom that has inflated the value of suburban homes - giving boomers a fat wad of cash if they choose to sell them - will start to change that. Within the next six months, a number of new housing ventures will be asking renters to pay $3,000 a month for a downtown apartment, or asking buyers to pay more than $400,000 for a city condominium. There are early signs that the wealth boom that has visited so many U.S. cities in recent years may be stirring in Hartford: At the Goodwin Estate in Hartford's West End - a new luxury development built around a historic mansion that a few years ago had decayed so much that it was home to a pack of wild dogs - the four homes that have sold for more than $500,000 during the first five months of 2005 match the number of homes that sold at that price in all of Hartford in each of the 2002 and 2003 fiscal years. When a suburban couple bought a 2,000-square-foot condominium in the mansion for $625,000 this year, appraisers were unable to find a comparable, per-square-foot sale in Greater Hartford, said Anne Francis, sales manager for Goodwin Estate. "I have just been floored [by the sales]," she said. "We have been doing very well." In the two weeks since the developers of The Metropolitan condominiums put banners on the side of the downtown building, they have received more than 250 inquiries from potential buyers for units that will run from $200,000 to $400,000. Saws screeched and drills whirred Friday as workers rushed to complete the sheetrock, flooring and tiles for two model units to open to the public this week. Trumbull on the Park, a 100-apartment complex that will open in October, has received about 40 reservations. Developers say the strongest demand is for units that will rent for between $2,000 and $3,200 a month. Someone able to spend $3,200 a month on housing could buy a very nice house in the suburbs: Realtors say that amount of money would cover roughly a $500,000 mortgage. But developers say they think lifestyle choices will drive the downtown market. "What I'm seeing is a lot of people that are just sick and tired of the suburbs," said Martin J. Kenny, the developer of Trumbull on the Park. "The anonymity of city life is appealing to people that have spent what seems like one lifetime in the suburbs. Not every mom wants to be a soccer mom forever. There's an afterlife." During the 1990s, as housing prices fell in Hartford and hundreds of owners walked away from properties that had bigger mortgages than the properties were worth, a venture like the 36-story Hartford 21 apartment tower, which will replace the Hartford Civic Center mall, would have been economic suicide. Rents have not been set yet, but apartments in the new tower will rent for at least as much as other new buildings in the city, the developers say. Where cities in other parts of the country, especially in the West and South, bolster their economies by the political annexation of fast-growing suburban areas, developers in Hartford now say they can help the city by annexing some of the region's affluent baby boomers and young professionals. "The goal has always been to import the affluence of the suburbs into the city," said Lawrence R. Gottesdiener, chairman and chief executive officer of Northland Investment Corp., who as the developer of the $162 million Hartford 21 project may be making the biggest real estate bet downtown. "What does Hartford need? It needs the affluence of the suburbs. But it can't geopolitically expand, so you are going to have to attract that affluence into the city." For decades, Connecticut's demographics have been tilted in favor of the suburbs. With the population bulge of the baby boomers in their 20s, 30s and 40s, the dominant demographic group was having children and raising them, primarily in the suburbs. "Suburbia is the archetype of the familiar private space, where you can feel in control and raise your family and have a real sense of safety. But when the children leave the nest, you may want an environment that is easier for you to access," said Todd Swanstrom, a professor of public policy at St. Louis University. "What you get is a kind of a housing mismatch, where you have these suburban homes on large lots that may not meet the lifestyle of at least some of the baby boomer generation when they reach retirement," he said. "They want to have amenities close to them, that fit their lifestyle, especially once the children have left." Like a fat kid stepping to the other side of a see-saw, the baby boomers are pushing a demographic shift in Connecticut. The number of state residents aged 45 to 59 - people in their peak earning years, who are less likely to worry about poor urban schools - grew by 13 percent over the past four years, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates. The number aged 25 to 39 - the group forming families and having children - dropped by 27 percent between 2000 and 2004. "Gentrification" was once a dirty word in American urban politics, but leaders such as Hartford Mayor Eddie A. Perez and civil rights lawyer John C. Brittain now say they are in favor of having more rich people in Hartford. Perez said that an influx of wealthier residents would not be gentrification unless they displaced poorer residents. The city is building a range of housing for working-class and middle-class residents, and could use more housing in the $350,000 to $750,000 range, Perez said. Even the new luxury housing planned for downtown would still make up only a small portion of the housing stock, he said. "Diversity is a good thing," Perez said, even if it means more Republican voters in Hartford. "It's OK. We'll finally have an election in town." Brittain, one of the lead lawyers in the Sheff vs. O'Neill school desegregation lawsuit, said the city would benefit by attracting more upper-income white people to projects such as Hartford 21. "I've changed my view, and I say it unabashedly in public," Brittain said. "Where I was an opponent of white gentrification in the '70s, I am now a supporter [of the idea] that you need to have a mix of racial - of particularly white racial, and certainly upper-income - integration in blighted urban areas in order to improve those areas, and improve everything else with it. "So I'm in favor now of some gentrification, with the proper safeguards for the adequate relocation of any existing tenants, including racial and language minorities," Brittain said. Swanstrom was the co-author of a recent study that found metropolitan Hartford was the most economically segregated city among the nation's 50 largest metropolitan areas in 2000. Hartford was the only metro area in the country in which city dwellers had less than half the income of suburbanites. And that means Hartford probably has a long way to go before it sees the kind of luxury-loft urban development that New York, Washington and other cities with superheated real estate markets have seen. The wealth gap between cities and suburbs tends to be more extreme in the Northeast than in the South and the West, where cities are more likely to be able to annex growing suburban areas. But even among compact Northeastern cities, Hartford stands out for its economic segregation, Swanstrom said. "The poor are unusually concentrated within the central city" and the wealthy outside the city limits, Swanstrom said. Even though the median sale price of housing in Hartford is up 64 percent since 2000, suggesting an influx of affluence, prices are still lower in the city than in almost all of its suburbs. Condominium units in neighborhoods such as Asylum Hill still sell for under $60,000. And one of the prime selling points for the Goodwin Estate is not the urban location; it's the proximity to West Hartford Center. There is not so much an influx of rich people into Hartford as an influx of middle-class people who made money on their suburban homes in the recent vibrant real estate market and are ready for a lifestyle change, said Thomas D. Ritter, the former speaker of the state House of Representatives, who recently bought a home at the Goodwin Estate. Goodwin Estate is not an age-restricted development, but Ritter said he knows of only one school-aged child in the 17-acre development of townhouses and condominiums. While many people are interested in city living, "a lot of people did not want to live here when their kids were in school," Ritter said. The complex is still under construction and won't be complete until the end of the year; only 10 of the 63 homes have yet to be sold. With their two children grown, Bob and Chris Healey traded their 3,100-square-foot home in Glastonbury for a 1,100-square-foot condo in the Goodwin mansion last year. They said they don't see themselves as part of an incoming wave of wealth. "I think of ourselves as being mainstream, just average bears, by no means affluent," said Bob Healey, a 59-year-old lawyer. The couple was the first to buy and move into a unit in the mansion, last September. "We're at that time in our lives when we can take more time for ourselves," said Chris Healey, also 59, who works at the Hartford Club. "We can take the time to see shows, and fine dining, and things like that in Hartford." Even though the floor area in their new home is small, they have 23-foot ceilings, and the couple said they gained a sense of freedom as they pared down their belongings. Bob Healey now has a 10-minute walk along Asylum Avenue to his office. He said he didn't count on how much pleasure he would get seeing the leaves change color last fall, knowing he wouldn't have to rake them. About a year ago, he was working out at the downtown Hartford YMCA and ended up talking to Bob Daglio. Both of them realized they were planning to sell their homes in the suburbs and move to the city. Healey and Daglio recalled how a guy on another exercise machine down the row piped up, Hey, we're planning to do that, too. So though they have met with their share of skepticism, the Healeys say, they have a sense that they are part of something building in Hartford. "I think everybody who has made the move here probably

was met with some comments like, `You're moving to Hartford?'" Healey

said. "Clearly, what you need [in Hartford] is for a critical

mass to develop, and without any claim of authorship, I'm sensing

that people are beginning to opt for this."

|

|||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 | |

|||

|