|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

Filling The Dental Gap UConn Works To Get More Minorities Into Dentistry To Improve Tooth Care For Poor December 17, 2006 By the age of 17, Jason Hernandez had dropped out of high school three times. He was hanging out, playing video games and skipping school, mostly because it was too much trouble to get out of bed.

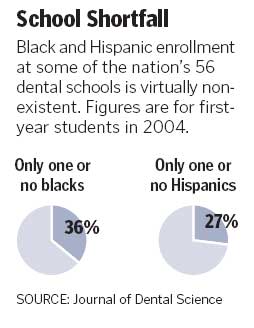

Now 28 and a student at the University of Connecticut's School of Dental Medicine, Hernandez is part of a national experiment designed to close the gap in dental care between the nation's haves and have-nots. In Connecticut, and across the country, only about one-third of low-income children get the regular dental care they need to prevent tooth decay and its consequences. It's even harder for poor adults to find a dentist. State and national leaders hope that by working with men and women such as Hernandez - blacks and Hispanics with promise, but perhaps a shortfall in their academic preparation - they can help solve a critical shortage of dentists willing to treat low-income patients. The premise is that minority dentists will be more likely to devote at least part of their careers to treating people in underserved communities. "We don't know all the reasons for this, but there is ample evidence that black dentists treat a much higher percentage of black patients and Hispanic dentists treat a much higher percentage of Hispanic patients," said Dr. Peter Robinson, dean of the UConn dental school. The program is being funded, in part, by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which four years ago awarded $15 million to 15 dental schools - including UConn - to find creative ways to attract more minority and low-income students into dental school. At UConn, Dr. Cynthia E. Hodge, associate dean of the dental school, spends her days identifying promising minority college students and getting them to consider dental careers. The students spend the summer before their senior year of college preparing for the tough national dental school entrance exam known as the DAT. In the first two years of the program, 12 students from colleges across the country spent six weeks at UConn practicing for the exam under Hodge's no-nonsense guidance. Eleven scored high enough to earn a spot in one of the nation's 56 dental schools. The students who are admitted to dental school begin their studies during the summer, giving them a two-month jump on the tough medical curriculum they face in the first two years of dental school. At UConn, the recruitment effort is showing dramatic results. Before 2002, the first year of the grant, about 6 percent of students accepted at the dental school in Farmington each year were black, Latino or Native American. In 2005, 29 percent of the incoming dental class was from so-called underrepresented minority groups. In Hernandez's class this year, one in five students is black or Latino. "It's like anything else in our society," Hodge said. "They will treat more people that look like them than don't look like them." A Different Path Hernandez learned early how uneven access to medical and dental care can hurt children and adults. His trouble in school started with a cracked lens in his glasses. He was in junior high school, a boy who loved algebra and played so hard on the basketball court that his glasses didn't stand a chance. Eventually, Medicaid cut off coverage for replacements and Jason went to school with tape on his lens - and got teased for it. When the taunting became too much, he left his glasses home. Unable to see clearly, Jason fell behind and continued tumbling through an uninspired school career. When it came to dental care, Hernandez was luckier than many. For most of his childhood, Connecticut paid dentists directly for each Medicaid patient they treated, and while the rates were low, some dentists were willing to participate in the state program. Dr. Ted B. Fischer saw the Hernandez family in his large private practice in Norwich. In bad times, he accepted their Medicaid card. In better times, when Hernandez's mother was working as a nurse's aide, her private insurance paid the bills. But in 1995, the state adopted a system of managed care for low-income families. And strict rules atop already low pay drove most private-practice dentists out of the program. For thousands of low-income Connecticut residents, including Hernandez, finding a dentist became next to impossible. At 19, with a job shelving videos at Blockbuster, Hernandez passed the high school equivalency exam and enrolled in a few community college courses. He found that good grades came pretty easily. He transferred to UConn. And last May, Hernandez graduated with a bachelor's degree in molecular cell biology. His grade point average was 3.57 - less than half a point shy of perfect. Hernandez was already considering a career in medicine when he went to Fischer's office with two impacted wisdom teeth four years ago. He had not been to the dentist since Fischer stopped accepting Medicaid. But the pain forced him to seek help. "He seemed really happy and he was able to alleviate my pain big time," Hernandez said of Fischer. Before his senior year of college, Hernandez enrolled in Hodge's special summer dental school boot camp. While Hernandez says it's too early to know what he wants to do with his dental degree, he said he'd like to combine private practice with teaching. Asked if he would accept Medicaid in his private practice, Hernandez was shocked to even be asked. "Of course," he said. Field Work In addition to recruiting black and Latino students, grant-funded dental schools are introducing all of their students to issues of racial disparities in health care and the challenges of working in a public health clinic. UConn's fourth-year dental students, for example, now spend about one-third of their clinical training in community health centers. Previously, many never even saw the inside of a clinic, said Robinson, the dental dean. And a number of graduates have chosen to work or take continuing education residencies at public health clinics, where earning potential is lower than it is for dentists who go into private practice. Dr. Damian Findlay is one of them. Coming into dental school, Findlay envisioned a career as an orthodontist in private practice, making a fortune putting braces on the teeth of children whose parents had good jobs and dental insurance. A rotation at the Charter Oak Health Center, a federally sponsored public health clinic in Hartford's impoverished Park Street neighborhood, changed his thinking. The son of immigrants from Jamaica who settled in Alabama to pursue doctoral degrees, Findlay never experienced the health care barriers so common in minority communities. But he enjoyed the challenge of finding a translator, completing a medical history and repairing the teeth of his Spanish-speaking patients in the one hour allotted at the Charter Oak clinic. And he has noticed how comfortable his West Indian patients seem to feel in his chair. He found that he enjoyed caring for the patients with HIV, hepatitis and cancer, whose teeth had become painful casualties of the diseases and treatments. The patients were desperate and there were so few community dentists willing to treat them, that they often were grateful for his care. Now, Findlay is considering devoting at least a portion of his professional life to treating patients who cannot afford care. "So much changes when you witness the access to care issues," said Findlay, who is completing a one-year postdoctoral residency in the charity dental clinic run by St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center in Hartford. "It's so much different when you see it rather than just read about it."

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|

More than a decade later, Hernandez is on a new path that may lead back to the kind of ragged, low-income neighborhood where he grew up. If he returns, though, it will be as Dr. Hernandez.

More than a decade later, Hernandez is on a new path that may lead back to the kind of ragged, low-income neighborhood where he grew up. If he returns, though, it will be as Dr. Hernandez.