|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

A Hospital Battle Is Brewing February 4, 2007 In a bid to preserve a fragile economic peace, top executives from three Hartford-area hospitals gathered at the Avon Old Farms Inn last April for a private meeting with officials from the University of Connecticut.

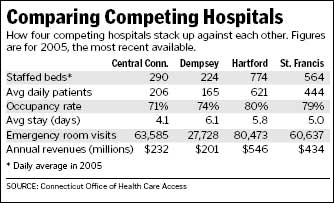

UConn was exploring a plan to dramatically expand John Dempsey Hospital in Farmington, a proposal officials at Hartford Hospital, St. Francis Hospital and Medical Center and New Britain-based Hospital of Central Connecticut argued would siphon off many of the affluent and well-insured patients who were keeping their institutions from drowning in red ink. Why not avoid a war? The talks, which continued sporadically throughout 2006, failed. Last week, UConn announced it would pursue a $495 million project to build a new 352-bed hospital in front of the existing health center. Dempsey, a 224-bed hospital built as a political compromise among feuding city hospitals more than three decades ago, and its role in Greater Hartford's health care community remains a bitterly contested issue. There was a time when some questioned whether the hospital was needed at all. But it is now an integral part of UConn's sprawling teaching and research complex, and officials say it is too small to remain economically viable and attract top-flight faculty. Building a new hospital is necessary for Dempsey's long-term survival, officials said. But foes of the new hospital say it will spur a sort of medical arms race as they seek to upgrade their own facilities and launch specialty clinics in suburban towns to compete for affluent Farmington Valley patients. And that might actually hurt consumers, they said. The expense will drive up health insurance costs to consumers and businesses as hospitals recoup their investment. And these changes will do nothing to improve quality of care for the poor, they say. "This puts everyone's bottom line at risk," said Laurence Tanner, president and chief executive officer of the New Britain-based Hospital of Central Connecticut. "In this environment, every ripple looks like a tidal wave." Over the past decade, no Hartford-area hospital had made much money, but, with a few exceptions, most avoided catastrophic losses. All of the hospitals in the region struggled to varying degrees with the burden of providing care for patients with Medicaid, the government program for the poor that now reimburses hospitals only about 70 percent of the cost of treatment. But the addition of any new beds in midst of the affluent Farmington Valley would make it difficult for other area hospitals to attract the privately insured patients who would help cover the shortfall, officials of the three hospitals told UConn. "When you plunk down something this big, it inevitably upsets the vital balance of the Hartford health care system," said Kevin Kinsella, vice president of Hartford Hospital. During last year's discussions, officials from the four hospitals jointly hired a consultant to assess the need for new beds in the region. Until a peace treaty could be hammered out, the CEOs promised UConn they would lobby the General Assembly to make up a projected $26 million shortfall in the Health Center's budget over the next two years. At one point, officials from the three competing hospitals even floated the idea that all four institutions join forces to build and operate a new hospital. "But there was never anything of real substance," said Dr. Peter Deckers, head of the UConn Health Center. Deckers and UConn officials decided that they could not afford to wait any longer. Dempsey is too small to train the school's medical students and does not hold enough patients to attract top-flight faculty who desire to open clinical practices, they say, and the 30-year old facility is already outdated and patients are complaining about sharing rooms. While the consultant's report projected the Hartford region would not gain much in population, it also showed that the region's residents will be older and make more hospital visits. The report suggested that the region directly served by Dempsey needs about 90 new beds by 2014 and its larger market - stretching from Litchfield to Manchester - will need 158 new beds. And looking beyond 2014, the health center estimates it will need 128 new beds in large part because much of the new demand for hospital services will come from its own backyard. "Whether [local hospitals] like it or not, all of the demand in the region is coming from the greater Farmington Valley over the next 30 years," Deckers said. "We simply need more beds." "Everybody wants to perpetuate what already exists in the Hartford market," Deckers said. "What everybody forgets is that if you have a better medical school, then everybody in the market benefits." The fight is now expected to move to the General Assembly, which will have to approve bonding for the $495 million project. It also needs approval from the Office of Health Care Access before construction can begin. The sheer magnitude of the UConn proposal - larger than the 90-bed expansion originally contemplated - stunned the local hospital officials. Not only would UConn attract new patients in their own backyard, but many of the privately insured patients who now are treated at institutions such as Hartford Hospital and St. Francis, Bristol Hospital and Charlotte Hungerford Hospital in Torrington. Given the precarious financial situation of most regional hospitals and the increasing burden of caring for Medicaid patients, the loss of even a small percentage of privately insured patients would be felt as far away as Waterbury and Manchester, Tanner said. Area hospital officials also do not buy arguments about the need for a huge hospital attached to the medical school. Harvard University in Cambridge and Brown University in Providence do not have their own hospitals and thrive working with urban hospitals, where most U.S. medical students still train, they note. Hartford and St. Francis already train about 70 percent of UConn medical students to the advantage of all institutions, they add. If the UConn plan is approved, hospital officials predict they would have to aggressively develop strategies to lure patients with private insurance. Tanner, for instance, predicts that hospitals will have to spend hundreds of millions of dollars in capital improvements to create their own private-room hospital beds to compete with UConn's new hospital. Local hospitals may also decide to renovate and expand their own hospital units - or create new facilities in the suburbs that offer specialties coveted by suburbanites, Kinsella said. The result might be duplication of services in certain areas and lead to millions of dollars in investments that would have to be recouped by higher hospital costs, which in turn would be passed on to businesses and consumers, he said. And those investments would also do little to meet the health care needs of poorer Connecticut residents, he acknowledged. Kinsella notes that Connecticut last commissioned a hospital development plan 22 years ago. Before the legislature guarantees more than $400 million in bonds for the UConn project, he said, the state should thoroughly examine how to meet the region's future hospital needs in ways that will not dramatically drive up the cost of care. "Rarely is a change made to a single institution as beneficial to the entire community the way a community solution would be," said Christopher Hartley, senior vice president of planning and facilities development at St. Francis.

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|