|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

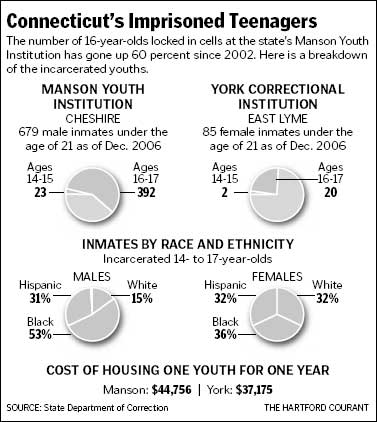

Alarms Raised On Youth Crimes Advocates Urge State To Invest In Prevention January 10, 2007 Anyone doubting an increase in youth crime and violence in Connecticut over the past year need only peek into the cellblocks of the John R. Manson Youth Institution in Cheshire. The number of incarcerated 16-year-old boys has increased by more than 60 percent since 2002, Mary Marcial, a deputy commissioner for the state Department of Correction, said during a symposium on youth safety Tuesday at the Legislative Office Building in Hartford.

On Dec. 1, 2002, there were 76 youths of that age locked up in Manson. Last year on the same date, there were 122. Connecticut is raising a generation without hope, said Elaine Zimmerman, executive director of the Connecticut Commission on Children, one in which families, schools and communities are increasingly unable to provide the resources struggling children in this state desperately need. It is a generation whose feelings were poignantly captured Tuesday in a New Haven fifth-grader's crayon drawing of people shooting each other, crying and lying in pools of blood on the street outside her home. "There is an overall sense that they don't know if the adults have it together, if they can be taken care of," Zimmerman said. "They don't know if they are safe." Zimmerman and other advocates Tuesday said they will push for a variety of prevention initiatives this legislative session, including funding to reduce truancy, create more after-school programs and increase summer employment for youths to keep them out of trouble. Expanding juvenile review boards and increasing funding to local youth service bureaus could also help divert youngsters from jails and detention centers, they said. Hartford Police Chief Daryl K. Roberts said adults need to raise their expectations of kids, listen to them and stop talking down to them. "A lot of young people don't feel like we care because that's what we show them," Roberts said. "We show them by our deeds, our words. ... If we expect them not to succeed, they will live by our standards." Roberts said he was able to become a police officer and ultimately chief because no one ever called his family "dysfunctional" and told him otherwise that he wouldn't succeed. "We need to raise our standards," said Roberts, who recently launched an aggressive anti-truancy initiative in his department. "We need to give young people a reason to succeed, not a reason for failure." State Rep. Toni Walker, D-New Haven, said many of the programs the state relied on to help children in the past aren't working. "Our children have changed just like you and I and the rest of the citizens of this state have changed," Walker told the attendees Tuesday. She said the state has to invest in programs that address family problems at their core. The state needs to do a better job, she said, keeping children in school, talking to them about their substance abuse problems and lining up services to address the issues affecting their families. Throughout the country, states are grappling with a rise in youth crime and violence. The latest national crime index from the FBI revealed that among juveniles under 18, murder arrests increased 20 percent from 2004 to 2005. Robbery arrests involving juveniles rose 11 percent after two decades of decline. African American youths have been hit hardest of late. Violent crime arrests for black youths consistently outpaced the growth among white youths in a recent study conducted by the Chapin Hall policy research center at the University of Chicago. Overall violent crime arrests for white juveniles dipped 3 percent between 2004 and 2005, but the rate for black youths increased 14 percent, according to the Chapin Hall report. In terms of more serious crimes, arrest rates for murder, robbery and weapons for white youths increased less than 5 percent between 2004 and 2005, yet jumped by more than 20 percent among black juveniles during the same period, the report said. State officials Tuesday emphasized that cooperation among different agencies will be key to many of the initiatives' success. They all pledged their support. "Education is a key player," said George Dowaliby, interim associate commissioner of the Department of Education. "Not only because [schools] take most of the kids we are talking about this morning, but because we know success breeds success." In Connecticut, Dowaliby said, when compared with their white peers, black males are 3.5 times more likely to be expelled from school; 4.5 times more like to receive an out-of-school suspension and 20 percent more likely to be special education students.

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|