|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

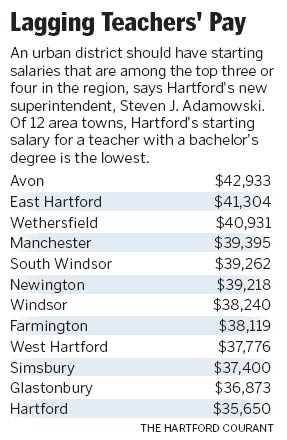

Schools Chief Has An Agenda Adamowski Sees 'Disparate Initiatives' In Hartford System November 27, 2006 Steven J. Adamowski's arrival in Hartford was delayed until today, but look for the new superintendent of schools to begin his promised shake-up quickly. The educator-in-chief - who starts work later than expected because of the recent death of his father - arrives with an agenda already in place. He and Mayor Eddie A. Perez, who doubles as school board chairman, warn there will be some pain before a growth in student achievement they are promising takes form. Human resources experts will have launched an aggressive hunt for talented teachers. There will also, he promised, be a vision in place to bring all students up to the state average for reading and for math, and to improve the rigor of high schools to prepare students for four-year colleges. "The district is a collection of disparate initiatives," Adamowski said. "There's nothing that holds it together." "Disparate" doesn't quite describe it, said Gerald Martin, president of the principals' union. "There's desperate initiatives. People are trying all kinds of things. There's been a lot of reliance on [individual] schools to lead the way. That's not leadership, that's followship." Some schools in Hartford have had success, drawing test scores that are competitive with suburban schools and earning federal recognition for excellence. But the secrets to their success remain just that: secrets, Martin said. "We have three `blue ribbon' schools," Martin said. "None of those principals presented to the other principals. How did that happen?" Adamowski is not the first Hartford superintendent to make big promises. Former Superintendent Tony Amato famously declared the district's standardized test scores would never be last again. There was some improvement, but after his departure, some of the district's scores slipped again to the bottom. The district of 24,000 students, with an annual budget of $215.9 million, has profound challenges, with more high school freshmen reading at the third-grade level than at the ninth-grade level, high absenteeism and student behavioral problems that vex even the most experienced teachers. Adamowski says he thinks the problems can be addressed. Hartford's size and its governance structure, with the mayor appointing most of the school board members, helped attract him to the district. "It has all of the challenges of an urban center, but the scale is manageable," he said. He will be paid an annual salary of $205,000 with a possible annual bonus of $20,000 based on reaching specific goals. Adamowski's plan for Hartford is similar to the strategy he used as schools chief in Cincinnati, a district about twice the size with many of the same problems. There he closed, redesigned and re-opened nine schools. He oversaw an improvement in test scores and a decline in dropout rates, and during his tenure the system was taken off Ohio's "academic emergency" list. Along the way, though, he angered teachers' union officials. He also clashed with teachers over a pay-for-performance program that eventually was rejected by the union. He said he may try again in Hartford. His plan to reshape certain schools would likely include redefining missions and replacing staff. Any schools that Adamowski decides to redesign will shut down over the summer. When they reopen, they will function under a new model, he said, such as the School Development Program created by James P. Comer, professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine's Child Studies Center. Comer's model creates school management teams involving parents and educators. It forces parental involvement through practices such as requiring parents to sign completed homework, and by assigning activities for parents to do with their children each evening. Perez supports Adamowski's plan. "Part of the reason we hired him is he has had to close, reconstitute and reopen schools," the mayor said. The district has been waiting for the bold moves Adamowski promises, Martin said. The federal No Child Left Behind law calls for the total redesign of schools that fail to improve after they're given assistance and time to improve. "It's supposed to happen," Martin said. But Ed Vargas, former union president, said he hopes entire teaching staffs won't be transferred out of failing schools. Wholesale transfers indict teachers who are doing a good job, along with those who aren't, he said. Another item on Adamowski's agenda is the quality of the city's high schools. "I'm very concerned about the high schools in general," he said. The large comprehensive schools have been reorganized into smaller "learning communities" with theme subject areas such as health or business. What seems to be missing in all this change, he said, is rigor. But, Martin cautioned, the high schools are Vargas said he's heard the cry for more rigor in the high schools time and again. "If we come up with high standards, then expect kids to flunk out," he said. "We're getting two messages: One from the state of Connecticut is `Water down the curriculum so kids don't drop out.' And then, when teachers water down the curriculum, they're told they're not rigorous enough. Mr. Adamowski is going to have to have the courage to stand by his conviction." Adamowski also has plans to revamp the teacher recruiting process in the city. Among other problems, Hartford has historically hired most of its teachers in the summer. "My general impression is the district is not as aggressive as it needs to be in teacher recruitment," he said. "You have to start recruiting early in the year, have relationships with schools [that train teachers] and be appealing to teachers in other towns. You cannot wait until the summer and hire teachers that are left over." In order for an urban district to be competitive, Adamowski said, it has to offer starting salaries that are among the top three or four highest salaries in the region. Out of 12 area towns, Hartford offers the lowest starting salary - $35,650 - for a teacher with a teaching certificate and a bachelor's degree and Avon offers the highest at $42,933. Perez agrees that Hartford does a poor job recruiting the best teachers. "We are always behind on the recruitment cycle to get the best teachers. Our second challenge is to reward them for their success so that nobody can steal them." There is room to raise salaries over time, Perez said, but he cautioned that "the well is not bottomless."

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|

more complex than the elementary schools. Teachers must deal with tough kids, gangs, large enrollments and many students who have trouble reading anywhere near grade level. "So many kids get to the high schools without the skills they need," Martin said.

more complex than the elementary schools. Teachers must deal with tough kids, gangs, large enrollments and many students who have trouble reading anywhere near grade level. "So many kids get to the high schools without the skills they need," Martin said.