|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

A Losing Battle, So Far Report: Reality Spoils Racial Balancing Act June 13, 2007 An agreement hailed four years ago as a way to end the overwhelming racial isolation in Hartford's public schools has failed, a new independent review of the landmark Sheff v. O'Neill school desegregation case says.

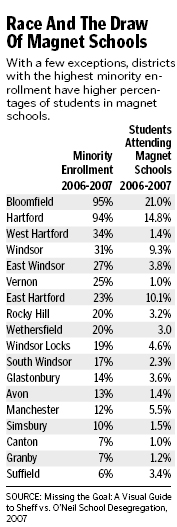

"This is sad news," said Jack Dougherty, a Trinity professor who, along with two students, compiled a report showing that the key Sheff strategies to reduce racial isolation in Hartford's schools have come up short. Shifting population patterns also have complicated efforts to balance schools by race. The report documents dramatic changes in many of Hartford's suburbs, including substantial growth in the number of non-white students since the Sheff case was filed in 1989. Several towns - Windsor, Manchester and East Hartford among them - have seen dramatic increases in their non-white student populations over the past two decades. "When the Sheff case was filed ... it was clear that people thought of Hartford as a minority city and the suburbs as predominantly white," said Dougherty, director of Trinity's educational studies program. "That model from 1989 doesn't fit nearly as well now as it did then." The report says a 2003 court-approved settlement in the Sheff case will fall far short of its goals when it expires this month.

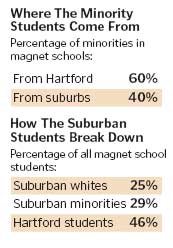

That tentative agreement, which also sets new racial quotas, requires approval by the legislature and the courts. A crucial piece of the earlier agreement revolved around magnet schools, where officials hoped that specialty themes, such as arts or technology, would attract white suburban children into the city, joining black and Hispanic children from Hartford. Instead, the magnets have been especially popular among families from towns such as Bloomfield, Windsor and East Hartford, where non-white students now make up a substantial majority of the school-age population. White families have been less enthusiastic about the magnets, with parents complaining about delays in the construction of new buildings, problems with busing and even a lack of sports programs. The city's struggles with crime, including a spate of shootings last summer, along with Hartford's troubled history of sub-par public schools, also have undermined recruiting.

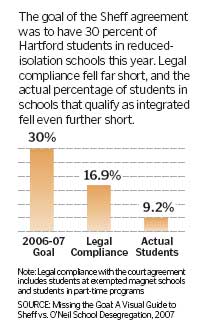

Sheff plaintiffs won a state Supreme Court ruling in 1996 and reached a settlement with the state in 2003 establishing a court-approved goal: enrolling 30 percent of Hartford's schoolchildren in racially integrated schools by this year. But Dougherty, along with Trinity students Jesse Wanzer and Christina Ramsay, reported that only 9 percent of the city's schoolchildren attend schools that have enough white students to qualify as racially integrated under the Sheff agreement. Even under a rule allowing the state to include children who attend recently created magnet schools that have not yet reached the minimum quota of white children, only 17 percent of Hartford children count toward the Sheff goal, the report said. The report also found that a long-running school choice program that allows Hartford parents to send their children to mostly white suburban schools is well short of its goal of 1,600 children. Enrollment in the program flattened out at 1,070 children this year, the report said. That is only one more than the program had a year ago and below the 1,175 students enrolled in 1979 in Project Concern, the predecessor of the current choice program. In some suburbs, enrollment in the choice program has declined over the past decade. Farmington, for example, enrolled 94 Hartford children this year, down from 108 a decade ago, the report said. The decline occurred mainly because the town's overall growth during the 1990s left limited space in its schools, said Superintendent Robert M. Villanova. As space problems ease, the town expects to take in more children in the program, he said. Sheff supporters lament the slow rate of progress in both the magnet school and the choice programs, contending that state officials have not provided sufficient support. In addition, they cite problems with busing and long delays in plans for building new magnets. "It has taken too long for [magnet] schools to be constructed," said city Councilwoman Elizabeth Horton Sheff, whose son, Milo, was the lead plaintiff in the landmark desegregation case. "You can't blame parents for being nervous, not having a permanent place for their schools," she said.

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|

Trinity College researchers will issue a report today showing in stark numbers how little progress has been made toward creating magnet schools that draw a mix of white and non-white students, or toward getting the city's mostly black and Hispanic student population into mostly white suburban schools.

Trinity College researchers will issue a report today showing in stark numbers how little progress has been made toward creating magnet schools that draw a mix of white and non-white students, or toward getting the city's mostly black and Hispanic student population into mostly white suburban schools. State officials last week announced a tentative agreement with the Sheff plaintiffs to take aggressive new measures to speed the pace of integration. A proposed extension of the 2003 agreement calls on the state to spend millions of dollars more over the next five years to subsidize magnet schools, charter schools and other programs designed to bolster integration.

State officials last week announced a tentative agreement with the Sheff plaintiffs to take aggressive new measures to speed the pace of integration. A proposed extension of the 2003 agreement calls on the state to spend millions of dollars more over the next five years to subsidize magnet schools, charter schools and other programs designed to bolster integration. Although a few magnets, including several older, well-established regional schools run by the Capitol Region Education Council, have attracted racially mixed student bodies, many others remain mostly black and Hispanic, the report shows.

Although a few magnets, including several older, well-established regional schools run by the Capitol Region Education Council, have attracted racially mixed student bodies, many others remain mostly black and Hispanic, the report shows.