|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

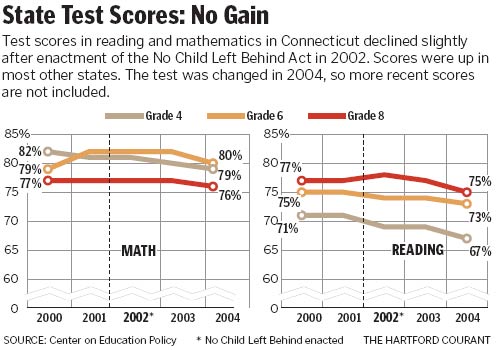

Test Scores Decline Slightly June 8, 2007 While students in most states made gains in reading and mathematics tests following the enactment of the federal No Child Left Behind Act five years ago, schoolchildren in Connecticut did not.

Connecticut was among only a handful of states where achievement test scores showed small declines on an independent nationwide study released earlier this week. "With mature testing programs, there tend to be gains in the beginning, but as the years go by, there are fewer gains," said Jack Jennings, president and CEO of the Center on Education Policy, a nonpartisan group that conducted the 50-state study. The center, based in Washington, D.C., spent 18 months gathering data to determine whether student achievement has increased since the enactment of No Child Left Behind in 2002. Among states with enough data to spot trends, 29 reported moderate-to-large gains in elementary school reading scores and seven others posted slight gains since then, but three states - Connecticut, Massachusetts and Missouri - reported slight declines. Nevada and Ohio reported moderate-to-large declines. In Connecticut, the declines were small. For example, 79 percent of fourth-graders met the mathematics proficiency standard in 2004, down from 81 percent in 2002. In fourth-grade reading, the proficiency figure dropped over the same period from 69 percent to 67 percent. Connecticut continues to have some of the largest gaps in performance for minority students, who trail whites by significant margins. "We had some closing of the gap, but generally we have not seen much improvement overall," said Thomas Murphy, a spokesman for the state Department of Education. The national study warned against drawing conclusions that any increase or decrease in test scores was the result of No Child Left Behind, saying that many other policies or factors could cause scores to change. In addition, comparing one state to another is virtually impossible because No Child Left Behind allows each state to create its own test and establish its own definition of proficiency. Nevertheless, Connecticut educators remain concerned about recent declines, particularly in reading scores, on state tests and on a national exam known as the National Assessment of Educational Progress. "We have to heighten our expectations and really bear down to see what the potential reasons are," said Mark K. McQuillan, Connecticut's new education commissioner. Of particular concern is the poor performance of many low-income and minority children, especially in the state's big cities, where the gap between them and middle-class white children is among the largest in the nation. In eighth-grade mathematics, for example, 86 percent of white students met the state proficiency standard in 2004, compared with 46 percent of black students and 48 percent of Hispanic students. "It's very disheartening to see that many African American students trapped in basic and below-basic categories. The same is true of the Latino population," McQuillan said. McQuillan has made the achievement gap a priority and has suggested changes such as a high school exit exam, tighter monitoring of local districts' performance and a longer school day and school year for struggling schools. President Bush and some members of Congress are seeking to renew the No Child Left Behind Act this year. The law called for a broad expansion of testing and a shake-up of schools that fail to make adequate academic progress for all groups of students, including low-income children, members of racial minorities, non-English-speaking children and students with disabilities. It also sharply increased federal spending on education. Supporters of the law say it has prodded schools across the nation to provide more help to low-performing students, but critics contend it is punitive. In Connecticut, Attorney General Richard Blumenthal filed a lawsuit challenging the federal law, contending it is not funded adequately. The case is pending. McQuillan said it is difficult to link test score gains directly to the federal law. "I don't know that you can make that claim," he said. "One could say it was simply the [extra] money as opposed to the testing strategy, but I do think expectations did rise because of the sanctions connected with the law. "I think that's been a very positive thing. It has certainly shown where some of the problems are in Connecticut."

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|