|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

The Truancy Epidemic Officials In City Struggle To Curb Chronic Absenteeism May 14, 2007 Adriana Reyes didn't feel safe at Hartford Public High School last year after girls beat her up in a bathroom, so she stopped going to school. She tried ninth grade again this year, but, distracted by drama in her friends' lives, she began skipping school. By March, she had racked up 28 unexcused absences -- the equivalent of nearly six weeks of school. Whenever Adriana skips, she has a lot of company. On an average day, school officials estimate, up to 2,000 Hartford children are absent from school without excuses -- nearly 10 percent of total enrollment. It is one of the key reasons why city schools lag the state in achievement test scores.

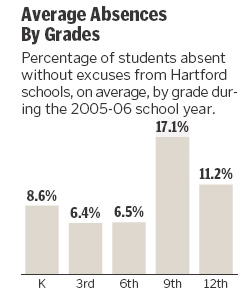

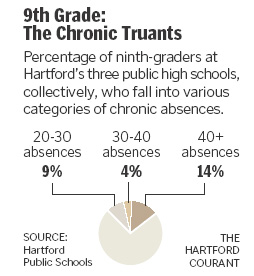

Educators, volunteers and police have stepped up initiatives to get children back into school, including truancy patrols, mentoring programs and interventions with parents. They have had limited success, but even some of those efforts are foiled by policies that clash. As volunteer mentoring programs expand, school budget cuts are eliminating the jobs of people who track truancy. Police take children off the streets and deliver them to schools, only to have some suspended for skipping school in the first place. Rules that call for referring chronic truants to the courts are enforced irregularly. And in a city where nearly 400 teenage girls had babies in 2005, most spots in a day-care program at one high school are taken by children of adults, not teen mothers. Missing Freshmen Truancy is most severe among ninth-graders. On an average day at the city's public high schools last year, 17.1 percent of freshmen were absent without excuses. More alarming, some educators say, is that nearly 9 percent kindergartners also were absent. Through January of this school year, 6.5 percent of kindergartners had been truant 20 or more days - the equivalent of a month or more of classes. "That's staggering," said Margie Gillis, senior scientist at Haskins Laboratories, a New Haven research institute specializing in language and literacy. "It has huge implications for reading. Kindergarten is no longer a play year. It used to be: Come to school and learn as you play. We don't have the luxury of doing that anymore." In a city with one of the nation's highest child poverty rates, efforts to curb truancy are complicated by a host of complex social problems, some of which erode parental supervision. Of Hartford's 36,000 children, a conservatively estimated 6,000 - one in every six - have at least one parent in prison. Most households are headed by struggling, single mothers. A truant boy tracked down by police told officers he was skipping school because the blisters on his feet made the walk to school too painful. He didn't own a pair of socks. Truancy experts cite four main reasons why Hartford children skip school: They don't feel safe at school. Students who must walk to school think their route is dangerous. Other walkers, many without suitable outerwear, find the trek too arduous on very cold or rainy days. Teenage mothers don't have day care. Truancy's link to academic failure is so critical that the state legislature is considering funding truancy programs to five districts whose dropout rates exceed the state average. Hartford could use the help. By April, more than one in four Hartford ninth-graders had missed the equivalent of at least four weeks; 14 percent had missed the equivalent of at least eight weeks. "The kids who are truant [in high school] have been truant their whole lives," said Kimberly DeSimone, director of school-based programs for The Village for Families & Children, a social service agency. Last spring, only 30 percent of Hartford third-graders were proficient in reading; only 29 percent of ninth-graders were reading at grade level. A study on Hartford truancy commissioned by the Center for Children's Advocacy, part of the University of Connecticut Law School, found that academic deficiency in high school was consistently linked to poor attendance in lower grades. And although the pattern of poor attendance starting in kindergarten and poor academic performance through middle school was evident, "early warning signs of future academic difficulty rarely led to a closer look." The study examined the records of 91 chronically truant high school students and found: 26 percent showed patterns of absenteeism as early as kindergarten and first grade; one student, by eighth grade, had missed the equivalent of more than two years of school. 84 percent tested far below their grade levels on Connecticut Mastery Tests in grades 4, 6 and 8. Still, the school district plans to eliminate attendance caseworkers from the elementary schools next year to cut costs. Suspensions In Hartford, school attendance is further eroded by suspensions, 13,000 of which were meted out by principals last year. The school board has asked administrators to develop programs to make time spent in both in-school and out-of-school suspensions educational. Meanwhile, the fight against truancy is enlisting troops from outside the school system. Hartford police and children's advocates are launching programs aimed at returning youngsters to school and keeping them there. After he was appointed last year, Police Chief Daryl K. Roberts said getting kids back in school was his top priority. But locating hard-to-find children - most of them failing - and returning them to school has had limited success. Of 99 children police had brought back to school by April this year, about half of them now attend regularly, Roberts said. He has directed patrol officers to pick up children on the streets and take them to school. Two full-time detectives and two school resource officers are assigned to visit the homes of habitual truants to investigate and point families to the help they need to get kids back in school. Police are focusing mostly on elementary and middle school students. If youngsters learn that school is optional, Roberts said, then "you think work is optional and you think rules are optional. Getting an education should not be optional." Truancy in kindergarten is the fault of parents, Roberts said, and under state law parents can be arrested for not sending their children to school. "I don't want to arrest a parent for not sending a child to school, but that is a parent's responsibility, and parents will be held accountable," Roberts said. Making Strides One volunteer program making strides is the Truancy Court Prevention Project, which monitors attendance, provides case managers for chronic truants, and informal, in-school talks between students and judges from state courts. Now in its third year, the project started with freshmen who had 40 to 45 absences - the equivalent of eight or nine weeks. "We found we couldn't turn things around with the resources we had," said Emily Breon, the project's director. In its second year, the project focused on students with 20 to 25 absences and succeeded in stemming further truancy. But it failed to help students improve academically. This year, the project added caseworkers from The Village for Families & Children and expanded to a middle school. At a recent truancy court session at Quirk Middle School, Superior Court Judge E. Curtissa R. Cofield, looking commanding in her judge's robe, mixed hugs and empathy with instructions. She told some students to keep an accounting of why they missed school and what they did with their time. She told them to join after-school programs. But some seemed desperately lost. One boy, whose father is "mostly in jail," is afraid to walk home from school because he was attacked. He is getting F's in math and science and a D in reading. What he enjoys, he said, is playing video games. Cofield tried to link the boy's success with games to an ability to concentrate. "Are you at high levels [in games]?" she asked. "Yes," he replied. "To get to those high levels, you have to invest a lot of time. I want you to invest that time in your life. I want you to be the champion of your life." Some students in the program continue to miss lessons, even when they're in the classroom. One boy told Cofield that he sleeps in class because he struggles with reading. He skipped science often, he said, because his teacher hurt his feelings by passing out tests to other students without giving one to him. "I feel like I'm invisible - like a ghost," he told Cofield. "I feel like I'm a nobody." High school caseworkers are having trouble helping teenage mothers - many of them eager to get back to school. Hartford Public High's school-based day care can accommodate eight babies and has a waiting list of 21. That list would be longer, one caseworker said, but when teens hear the number already waiting, they just give up. Some slots go to the infants of adults, not to the babies of teens. And rather than increase slots for students' infants, the high school spends resources on a preschool for toddlers - all children of adults. Meanwhile, Adriana Reyes is trying to get back on track in Hartford Public's truancy court project. She promised Appellate Court Judge Douglas S. Lavine that she would meet with all her teachers to talk about making up work she missed in her 28 unexcused absences. A couple of days later she was suspended for being in the hall without a pass. So make that 31 days of school missed by the end of March. And counting.

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|