|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

Missing Children City's Specialty Schools Struggle To Draw Enough White Students To Break Racial Isolation April 1, 2007

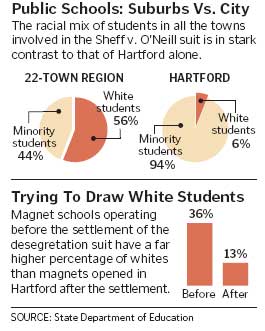

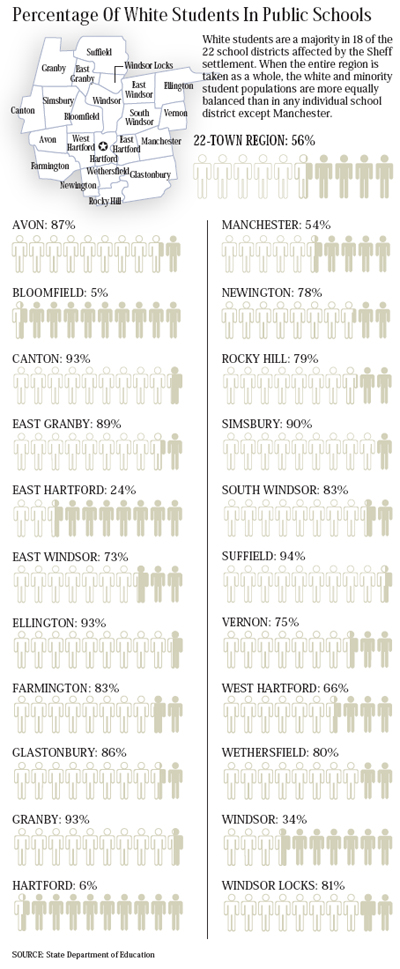

But Maya, one of only three white kindergartners at the school, isn't coming back next year. Four years after a landmark legal settlement was signed in the hopes of reducing racial isolation of blacks and Hispanics in Hartford schools, the effort is still missing a critical ingredient: White students. The centerpiece of the court-approved desegregation plan designed to resolve the long-running Sheff v. O'Neill lawsuit was the creation of new, specialty magnet schools, such as Annie Fisher, that, in theory, would draw a mix of white students from the suburbs and minority students from the city. The effort, so far, has proved popular among black and Hispanic students - from both Hartford and racially mixed towns like Bloomfield and Windsor - who have been drawn to schools focusing on themes such as the arts and technology. But white students from the capital city's suburbs have been far less eager to embrace the new schools. At the nine schools created since the Sheff agreement was signed in 2003, the population of white students ranges from a low of 4 percent to a high of 19 percent. The reasons vary. Parents worry about delays in the construction of new buildings, problems with busing and even a lack of sports programs. The city's struggles with crime, including a spate of shootings last summer, along with Hartford's troubled history of sub-par public schools, also have undermined recruiting at even the most promising magnet schools. "One of the hurdles is just the media and what people see on the news every night," said Delores Cole, principal at the Noah Webster Microsociety Magnet School, in a newly renovated building in a quiet West End neighborhood. "Once [parents] come, once they see the school, once they meet the teachers," Cole said, "they fall in love with it." In the case of Maya Kugel, who lives in Rocky Hill, Annie Fisher School had plenty of appeal, especially its all-day kindergarten program. But she is leaving because her parents grew frustrated with poor school bus service.

Old Vs. New Magnets There are two main types of magnet schools in and around Hartford, some operated by the city and others by the Capitol Region Education Council, a regional agency known as CREC. The magnet school approach has had more success attracting white students to older, well-established magnets in the Hartford region, such as CREC's Two Rivers Magnet Middle School in East Hartford, where whites make up almost half the student body. At Hartford's Breakthrough Magnet School, which moved last fall into a state-of-the-art, $29.5 million building, more than a quarter of the students are white. Breakthrough built a solid reputation after opening as a charter school in 1998. But the Hartford public school system has struggled to enroll whites at the nine magnet schools established since the Sheff settlement. Not one of the nine has enrolled enough white students to meet the 26 percent quota in the settlement. As a result, officials will not meet the Sheff goal of enrolling at least 30 percent of Hartford schoolchildren in integrated schools by the end of June, when the first phase of the settlement expires. Lawyers are in negotiations to extend the agreement and establish new goals. State and city officials say they need more time to make the magnets work, but progress has been halting, at best. Some of the new magnet schools remain almost entirely black and Hispanic. "Definitely a very, very poor job," said city Councilwoman Elizabeth Horton Sheff, whose son, Milo, was the lead plaintiff in the landmark desegregation case. "The school itself was great - great teachers, all of that, but it was the football," said 16-year-old Eric Syme, a white student who spent a year at the University High School for Science and Engineering, a Hartford magnet school, before withdrawing last fall to play football in his hometown high school in Rocky Hill. He also switched to a half-day magnet program, taking morning classes at the Greater Hartford Academy of Mathematics and Science, a CREC school. University High School, affiliated with the University of Hartford, has a fledgling sports program with soccer, cross-country and basketball, but the small school of 320 students does not expect to field a football team. "I lost two boys because of football this year," said Elizabeth Colli, the school's principal. The school boasts a rigorous math and science curriculum and promotes activities such as a popular robotics team and a fuel cell competition, but, only in its third year, it still faces growing pains. Like several other magnet schools, University High School is operating in temporary quarters. It is awaiting construction of a new building on the University of Hartford campus. "They really didn't have a school yet," said Jennifer Zakrzewski of Plainville, whose son, Dylan Landry, returned to his hometown high school after only three weeks at the magnet in 2004, the year the school opened. Landry is white. "He got there. He got calls from his friends at Plainville High School who wondered where he was," she said. "He was getting on a bus with one other guy. ... I think he missed his friends, being able to come [to school] at a normal time and play sports." In a recent survey by Trinity College students, researchers found that several white families considering magnet schools expressed dissatisfaction with their local schools, hoping the magnets would provide a better alternative. Still, like most Hartford schools, all of the city's new magnets, except for University High School, have failed to meet the standards of the federal school reform act known as No Child Left Behind. Overall, the city has some of the lowest scores in the state on the annual Connecticut Mastery Test. "That concerns me, and I think it concerns a lot of suburban parents," said David Therrien of Newington, who attended a magnet school recruiting fair in Hartford with his wife, Karyn. The Therriens, who are white, were looking for a school for their 10-year-old son, Jared - possibly a school with a science theme or something emphasizing drama and music. "We think he's not sufficiently challenged where he is right now," Therrien said. A Tough Sell While some of the schools, such as University High School, are newly created magnets, the toughest sell, according to school officials, are schools such as Annie Fisher and Simpson-Waverly - former Hartford neighborhood schools that were converted to magnets in wake of the Sheff agreement. At Simpson-Waverly, once hailed as one of the city's best schools, whites account for less than 5 percent of enrollment. At Annie Fisher, the racial makeup is much the same as when Milo Sheff was a fourth-grader there 18 years ago - the year the lawsuit bearing his name was filed. Last fall, only 11 white students were enrolled, about 4 percent of the student body. Like Maya Kugel, the Annie Fisher kindergartner, some suburban students have run into trouble with busing as magnet schools cope with the staggering logistics and cost of picking up and dropping off children from more than two dozen towns. "I know we lost a lot of people, especially our Caucasian students," because of busing glitches, said Delores M. Bolton, who heads the magnet school office for the Hartford Public Schools. Ronald Coles, Annie Fisher's principal, agrees that transportation has been a problem but is optimistic that his school will attract significantly more white children, especially by the time a planned $38 million renovation is completed. He projects that the school's white enrollment will triple by next fall and said, "Once that construction kicks in, we're going to get what we need here without any problem." Haphazard Effort The low numbers are distressing to Sheff supporters, who say the state - under a state Supreme Court order to address racial imbalance in Hartford's schools - has failed to provide adequate oversight or support to the magnet school efforts. The Sheff plaintiffs contend the magnet system has developed haphazardly, with one system and set of rules for magnets run by the Hartford public schools and a separate system of regional magnet schools operated by CREC. The two systems have separate selection lotteries, separate financial systems and separate busing programs. CREC, with a longer history of running magnets, has had more success in attracting white suburban families despite a chronic budget crunch and a reluctance by some suburbs to send students. Unlike Hartford, CREC requires towns to pay a tuition subsidy, causing some towns to limit the number of students or to opt out of the magnet program entirely. While Sheff supporters lament the slow pace of progress, city and state education officials say the goals in the original 2003 Sheff settlement were too ambitious and that there was little chance that newest magnet schools could be running at full speed within four years. And, despite the problems, magnet officials remain hopeful that white enrollments will continue to grow. At the Greater Hartford Classical Magnet School, black and Latino students make up nearly all of the junior and senior classes, but substantial numbers of white students are enrolling in earlier grades, making up 23 percent of this year's incoming sixth-grade class, for example. Among them is Sierra Szkrybalo, 12, of Glastonbury. "The kids there are from all different towns. ... I thought that was really cool," said Sierra, who takes a 45-minute bus ride to get to the school, in a $36 million new building in Hartford's Asylum Hill neighborhood. Tim Sullivan, Classical Magnet's principal, said the school also has begun to attract white students "who live in Hartford who typically attended private schools. We're competing with Northwest Catholic, Watkinson, [Kingswood-Oxford]." Still, getting the word out to more white students is a tough order. At a magnet school recruiting fair earlier this year in Hartford, one of the few white students was 13-year-old eighth-grader Sean Priest, who came with his parents from East Hartford to look for a high school. "I enjoy working with computers," he said, picking up brochures at a display booth and chatting with recruiters from the Pathways to Technology magnet school. Recruiters for Pathways, where white students account for 11 percent of enrollment, greeted Sean enthusiastically, telling him about the school's emphasis on technology, its small classes, and the promise of a new building scheduled to open in 2008. Less than two weeks later, however, controversy erupted over the site of the school in Hartford, where earthmovers already had begun to dig. Construction has halted while officials debate where the school, now operating in temporary quarters in Windsor, should be located. Sean Priest, meanwhile, still plans to attend Pathways in the fall. "We're keeping an eye on [the building controversy]," said Mary Priest, Sean's mother. "We're a little concerned, but it's not going to change our decision."

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|

Six-year-old Maya Kugel is among the first of what Hartford officials hoped would be a stream of suburban white children enrolling at Annie Fisher School, long a symbol of racial isolation in the city.

Six-year-old Maya Kugel is among the first of what Hartford officials hoped would be a stream of suburban white children enrolling at Annie Fisher School, long a symbol of racial isolation in the city. "That's been our biggest nightmare since, literally, day one," said Brian Kugel, Maya's father. "Sometimes it's like a crapshoot. You don't know if that bus is going to show up."

"That's been our biggest nightmare since, literally, day one," said Brian Kugel, Maya's father. "Sometimes it's like a crapshoot. You don't know if that bus is going to show up."