|

|

|||

|

||||

| Web Sites, Documents and Articles >> Hartford Courant News Articles > | ||

|

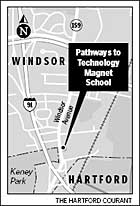

Battle Over School Site Raged Out Of View Behind-Scenes Forces Opposed Pathways Move February 28, 2007 Hartford officials' effort to build a new home for a magnet school collapsed in recent weeks after loud and public criticism by the city's representatives in the state legislature, who said heavy traffic made the location unsafe.

Ritter's interests are less clear, but the involvement of the former House speaker is troubling to those who had hoped to see the new Pathways to Technology school built at the corner of Broad Street and Farmington Avenue. Ritter, retained by Wertheim in 2004, says his formal status as the landlord's lawyer ended a year or so ago - but the Democratic powerbroker has remained involved: He approached Hartford Mayor Eddie A. Perez in late 2006 about the city continuing to occupy, or perhaps even buy, the Windsor building. And as recently as Jan. 25, Ritter surfaced at a private meeting with legislators, organized to discuss opposition to the site. The episode offers a rare insight into the difference between the public face of a debate over the future of a school - and the private one. Ritter's paid work as a private businessman's lawyer, combined with his unpaid efforts as a strategist, are a classic illustration of how political and personal networks can be used in attempts to affect government decisions. It is unclear how much of a role Ritter or Wertheim actually played in scuttling the mayor's plans for a $30 million, state-funded school on a 2.4 acre triangle between two major city thoroughfares and I-84. The opposition to the site was widespread - among legislators, the governor, and the community at large - largely because of safety and traffic concerns. But some argue the site's problems were political. "I really think that this whole project was a victim of politics," said Bernie Michel, chairman of the Asylum Hill Problem Solving Revitalization Association. "This was not democracy's finest hour." Ritter's "realm of expertise," he said, "is button-holing legislators who know him and maybe owe him a favor." A `Private Citizen' The Pathways to Technology Magnet School, initially created as an academy at Hartford Public High School, has been occupying temporary quarters in Wertheim's Windsor building since 2004, though the plan was always to find a permanent home in Hartford. That same year, Wertheim hired Ritter as his lawyer. Ritter said he represented the landlord's partnership, 184 Windsor Ave. LLC for "a small fee" to inquire with city officials about keeping the school in Windsor. Ritter said he stopped representing Wertheim more than a year ago, when the city made it clear it did not wish to extend the lease. Perez and others in Hartford were locked-in on the Broad Street site, believing the proximity to downtown businesses make it a perfect location. But there was a legislative stumbling block: Hartford's deed to the former state land allows it to be used only as a park, as a public safety complex or for economic development. The city's legislative delegation, citing safety concerns, blocked Perez's attempts to amend the deed and advance the project last spring. By last December, with another legislative session looming, Ritter requested a meeting with Perez at city hall. The subject of the Dec. 15 meeting, Perez said, was the Windsor building. Perez said Ritter "asked if we would change our mind ... [and] reconsider" a proposal that Wertheim had made a couple of years earlier: that the city extend the lease, which expires this August, or buy the building outright. Perez said he told Ritter no. Perez's chief of staff, Matt Hennessy, the only other one there, said it was clear to him that Ritter was speaking on Wertheim's behalf. "My impression was that he was there representing his client, who is the owner of the [Windsor] property," Hennessy said. Ritter insisted that wasn't the case. He said he was acting as a "private citizen" at that meeting - not as a lawyer or lobbyist - because Wertheim was not paying him and had not been his client for a year or more. But, he added, "I was not representing [Wertheim] at the time." "I can do things that I want to do, any time I want to do it," Ritter said. During the meeting in the mayor's office, Ritter also mentioned "his intention to discuss the issue of Pathways with legislators," Hennessy said. Opposition continued to brew among Hartford's lawmakers, and Perez tried another tactic: On Jan. 17, he wrote to state officials and said the city's position was that the magnet school was "economic development" - permissible without any legislative changes to the deed. He was prepared to move forward. Not so fast, replied state education officials, who told the mayor Jan. 24 that Attorney General Richard Blumenthal had to sign off on the mayor's interpretation. Undeterred, Perez began construction on the site. Closed-Door Meeting As Perez's efforts to start building were playing out in the press, an under-the-radar meeting about the future of Pathways was taking place. In attendance were several lawmakers, an aide or two - and Ritter. The Jan. 25 meeting was set up by state Sen. Jonathan Harris, D-West Hartford, who said he has talked many times about the school issue with Wertheim, a fellow West Hartford resident. "He's a constituent," said Harris, adding he is also interested in the issue because of his membership on the appropriations committee, which scrutinizes state expenditures, and his town's relationship with Hartford. State Rep. Marie Kirkley-Bey, D-Hartford, who has led the opposition in the General Assembly to the Broad and Farmington site, was also at that meeting. Her opposition carries weight because the site is in her district. Kirkley-Bey is close to Ritter, calling him "my mentor." She was promoted to an assistant majority leader's position during Ritter's six-year tenure as speaker of the House, and her daughter was hired into a legislative staff position the same day Ritter became speaker Jan. 6, 1993, records show. Kirkley-Bey said last week that she didn't need Ritter to convince her the site is unsafe. At the same time, she acknowledged that in addition to meeting with him Jan. 25, she had repeatedly consulted Ritter over the past year about strategy for blocking legislative moves to advance the plan. Ritter said he never served as Wertheim's lobbyist at the General Assembly. He said he didn't need to register on Wertheim's behalf, as he has with other clients, because he wasn't being paid. Asked why he attended the Jan. 25 meeting, if not to represent Wertheim, Ritter said he was a private citizen invited by Harris' Senate office staff, perhaps because he has decades of familiarity with the site, which he once proposed for use as a public safety complex. "I was asked my opinion," he said. Harris said he couldn't remember who had the idea of calling the Jan. 25 meeting. He said that it could have been Wertheim, Ritter or Kirkley-Bey but that if he "had to guess," he would say it was Wertheim. Wertheim did not attend. Harris said he also didn't recall if Ritter learned directly from his staff that the meeting was being set up, or if "I let Mark [Wertheim] know, and [then] Mark let him know." The meeting had no formal outcome, but enabled opponents of the site to consult about "alternatives" to the Broad Street site, as well as "what the mayor was doing." Last week, Wertheim deflected questions about his conversations with Harris, saying, "You'd have to ask Jonathan Harris. It's none of your business." "I'm not interested in parsing this relationship," he said. This isn't the first controversy for Wertheim or his building, a former home furnishings mall off I-91 in Windsor. In 1998, he and his wife, Allicia, friends and political backers of then-Gov. John G. Rowland, were awarded a lease under which the state pays $838,000 a year to house the headquarters of the State Board of Education and Services for the Blind in the building. The magnet school moved into the same building. The Wertheims' lease with the state raised questions from the start for reasons that included the Rowland campaign fundraiser they held shortly before they got the deal. Blumenthal later investigated the lease - and issued a report saying it was a "sweetheart deal" that Rowland administration officials allegedly "rigged" for the Wertheims. A Wertheim lawyer denied that at the time. In 2004, state Public Works Commissioner James T. Fleming signaled that his department would not renew the state lease. But the agency for the blind is still in the building, renting it on a month-to-month basis, and efforts to relocate it have failed so far, a Fleming aide says. How Much Influence? Ritter minimized his own influence in the Pathways debate. "I don't think there was anybody who took a position [against] this based on me," he said. The problem, he said, is that Perez pushed for "a bad site." In addition to Kirkley-Bey, other Hartford lawmakers said they opposed the plan without Ritter's prompting. "I was heavily lobbied by area insurance companies adjacent to the site. ... They weren't supportive," said Rep. Art Feltman, D-Hartford, who is one of Perez's challengers in this year's mayoral campaign. Other officials weighed in on the Pathways issue as well. Gov. M. Jodi Rell raised concerns about traffic. Blumenthal rejected Perez's "economic development" argument, effectively halting construction at the site. But others question if it was - in the end - concerns about traffic and safety that really killed the mayor's plan. "This is the other side of the story, given the actions of a few self-interested people," said Carl Nasto, deputy corporation counsel for the city. "He [Wertheim] went to the legislature and torpedoed our efforts." If no other option for the magnet school is found, city officials say, Hartford may need to keep it in Windsor longer than planned. And some residents of Asylum Hill are still upset about the activities of Ritter and Wertheim. Michel, the Asylum Hill group's chairman, said Wertheim, in hopes of "preserving his [rental] income," misstated the position of key state officials while arguing against the Farmington and Broad site. In an e-mail dated Dec. 10, 2005, to Michel, a copy of which is included in city records, Wertheim said that state Department of Education counsel Mark Stapleton "in particular" was opposed to the site, and that the department "would rather see the Pathways school remain in Windsor." Stapleton, chief of the education agency's office of legal and governmental affairs, said last week that he was "pretty annoyed" at Wertheim's statement. Stapleton said Ritter called him a couple of years ago to say Wertheim wanted to sell the building to Hartford, and asked if the city could get state magnet school funds for a building out of town. "I told him `yes,'" Stapleton said. "But the choice of a site is up to the [local] board of education. ... I would never want it to look like I was steering a site. ... It's out of character and I wouldn't do it."

|

||

| Last update:

September 25, 2012 |

|

||

|

But another force, not loud or public, has been working against the site: the combined efforts of influential Hartford lawyer-lobbyist Thomas D. Ritter and his onetime client, the landlord of a building in Windsor where the school rents space.

But another force, not loud or public, has been working against the site: the combined efforts of influential Hartford lawyer-lobbyist Thomas D. Ritter and his onetime client, the landlord of a building in Windsor where the school rents space.